Speculation: Eternalism and the Problem of Evil

Heres some speculation. I dont claim its all true, but I do find it interesting. And who knows? Maybe it is true.

As a man in his 70s, I often reflect on the past. Of course, sometimes I think about things I wish I hadnt done, things I wish I had done, or things I wish I had done better. But sometimes I merely recall people and places I once knew. I wonder if the past, in any sense, still exists. Or is the past utterly gone?

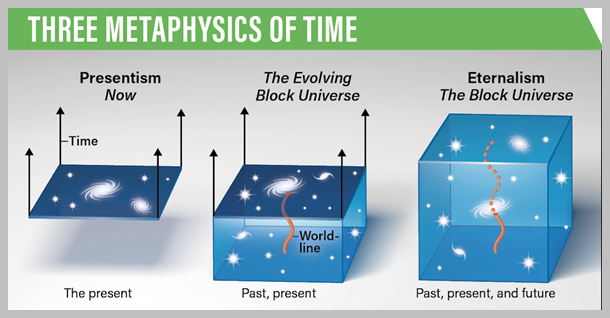

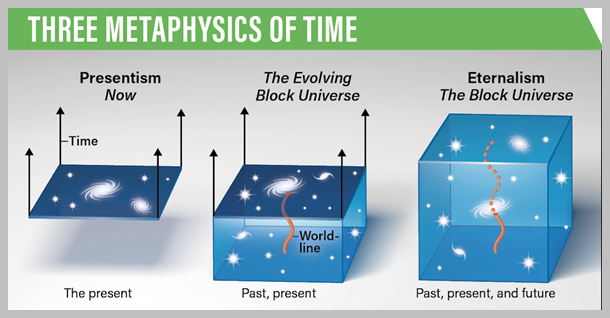

In two of three views of time, the past does exist. The image is from an article.

The struggle to find the origins of time

https://www.astronomy.com/science/the-struggle-to-find-the-origins-of-time/

If the past exists and if I exist in some sense after death, then can I return and re-experience some of my life's events and situations? As a disembodied consciousness, can I somehow reenter the stream of time and re-experience my life? Can I experience the lives of other people? Might I be able to experience all or part of someones life, much like watching a movie? (except Id be experiencing a 3D movie and also experience the persons inner thoughts and feelings whose life it was.)

Some scientists believe free will does not really exist. This view accords with Eternalism where any life already exists somewhere in the Block Universe. Its as if all existence is an enormous pre-recorded DVD and all we can do is watch and experience. Thus, no free will.

However, if we can choose which life (or which portion of a life) we experience, then we do have free willwe are free to select in advance what we shall experience.

It might be asked why someone would choose to experience a horrible, painful life. An answer might be that we often choose to view pain and disappointment and even horror in movies we watch. After all, it would be easy to make a two-hour movie of 100% wholesome sweetness: butterflies on a summer day, ocean waves gently rushing to shore, etc. But we dont have that. It seems we need some drama. Even in melodrama theres conflict and sadness: will Trish qualify for the cheerleading team? Will little Johnny get the iPad he wants for his birthday or not?

So, perhaps, as a disembodied consciousness, I selected the life Im experiencing now. Next time around, I could experience Abraham Lincolns life, Elvis Presleys life, or anyone elses life. Anyone disembodied consciousness can experience any portion of any life.

Also, under this view, there is no problem of evil. Someone who experiences a horrible life is akin to someone who chooses to watch a horror movie.

I find this view interesting but not entirely satisfactory. I still feel that many horrors should not happen. No child should get cancer, for instance. But if I have no free will, I cant help feel the way I do.

As a man in his 70s, I often reflect on the past. Of course, sometimes I think about things I wish I hadnt done, things I wish I had done, or things I wish I had done better. But sometimes I merely recall people and places I once knew. I wonder if the past, in any sense, still exists. Or is the past utterly gone?

In two of three views of time, the past does exist. The image is from an article.

The struggle to find the origins of time

https://www.astronomy.com/science/the-struggle-to-find-the-origins-of-time/

If the past exists and if I exist in some sense after death, then can I return and re-experience some of my life's events and situations? As a disembodied consciousness, can I somehow reenter the stream of time and re-experience my life? Can I experience the lives of other people? Might I be able to experience all or part of someones life, much like watching a movie? (except Id be experiencing a 3D movie and also experience the persons inner thoughts and feelings whose life it was.)

Some scientists believe free will does not really exist. This view accords with Eternalism where any life already exists somewhere in the Block Universe. Its as if all existence is an enormous pre-recorded DVD and all we can do is watch and experience. Thus, no free will.

However, if we can choose which life (or which portion of a life) we experience, then we do have free willwe are free to select in advance what we shall experience.

It might be asked why someone would choose to experience a horrible, painful life. An answer might be that we often choose to view pain and disappointment and even horror in movies we watch. After all, it would be easy to make a two-hour movie of 100% wholesome sweetness: butterflies on a summer day, ocean waves gently rushing to shore, etc. But we dont have that. It seems we need some drama. Even in melodrama theres conflict and sadness: will Trish qualify for the cheerleading team? Will little Johnny get the iPad he wants for his birthday or not?

So, perhaps, as a disembodied consciousness, I selected the life Im experiencing now. Next time around, I could experience Abraham Lincolns life, Elvis Presleys life, or anyone elses life. Anyone disembodied consciousness can experience any portion of any life.

Also, under this view, there is no problem of evil. Someone who experiences a horrible life is akin to someone who chooses to watch a horror movie.

I find this view interesting but not entirely satisfactory. I still feel that many horrors should not happen. No child should get cancer, for instance. But if I have no free will, I cant help feel the way I do.

Comments (223)

:death: :flower:

There was a researcher by the name of Ian Stevenson who devoted many decades to interviewing children who claimed to have recalled their previous lives. (His research is needless to say highly controversial and most often furiously rejected.) Anyway, I read a book about his life and work, by a journalist named Tom Shroder (Old Souls) who gives details of a few of Stevenson's cases. The thing that struck me is that is how ordinary the lives and circumstances of all these cases were. They were often in very poor familiies, more typically in the East, where belief in re-birth is socially acceptable (it's not, in much of the West.) Their remembered lives (and often deaths) were as mechanics, villagers, laborers, soldiers - none of them remembered being the Queen of Sheeba or Wizard of Oz. One of the cases Shroder recounts is of a Lebanese mechanic who had died in his late teens in a sports-car accident. The child who remembered that life was born in a village not far from the site of the accident, and remembered many details of his previous life. (Most of these recollections are said to be lost very soon after a child learns to speak, making the window of opportunity for research a very brief one. They usually first present with the child declaring that 'this is not my home', 'you are not my parents', 'this is not my name', and so on.)

Quoting 180 Proof

In accounts of bardo states in the Buddhist literature, one of the warnings is that beings in the between-death states become attracted to forms in that state that are associated with the lower states of being. These include not only being reborn in the animal realm - you read in Zen literature the occasional admonition, that 'you will find yourself in the womb of a cow!' - but also hell states and the realm of hungry ghosts (which the pointed structures on roofs in Asian villages are intended to ward off.) I'm not persuaded that it is true, but I will admit it scares me. :yikes:

It depends on whose perspective. If ours, then it's gone. We are all traveling on the same speed of light. We are all changing and carrying with us just the memories of the past. If you used to live at A street 20 years ago, and you left that place, then your past will only exist in memory.

Recently some news announced the arrival of a radio signal that started traveling some 8 billions light years ago. If our past could be captured in some radio signal and hologram, then another life forms in another galaxy could see our past. But we wouldn't see our own past.

Edit. I am responding to the quoted line above as I understand it literally -- not some reincarnation.

My perspective on time aligns more with Presentism, which posits that time only exists in the present moment (the eternal now of the Tao). The past and future are not tangibly present, but are instead represented by memory and imagination. I think that the past as well as the future is contained within the present as information, and that it may be possible to simulate past events to some degree of fidelity using advanced virtual reality technology that is not yet available. This kind of simulation could potentially provide the closest experience to time travel by allowing individuals to re-experience past events in a simulated environment. I do not believe true time travel in the usual sense is possible.

The plausibility of simulated time travel may be precluded or challenged by the existence of free will, as the accurate determination of past and future events from the present state would require a deterministic universe. While the universe i believe for the most part is deterministic, the occurrence of quantum events at the Planck scale may introduce some level of indeterminacy.

Quoting Art48

This reminds me of one of my favorite TV shows back in the 90s: "Quantum Leap".

Well, we could always speculate about such a thing.

Quoting Art48

We dont choose a whole life or even a portion of it. What we choose is a scheme of understanding that we place over events in order to try and make sense of things. Those schemes dont tell the events how to affect us, they act as wagers that events will unfold in a way that bares a reasonable resemblance to how our schemes anticipate their unfolding ( the most important of these events being the behavior of other people) . If the flow of events validates our constructions of them by being relatively consistent with our expectations, then our schemes has staying power, and avail us of intimate connection with others.

Nevertheless, we are always having to make adjustments to our schemes, sometimes only minor repairs but other times major overhauls when we find ourselves in the midst of an emotional crisis. Despair, confusion and massive anxiety are all signs that our scheme is no longer working for us and we are faced with a major reorganization of our constructs. The only way forward from here involves much experimentation and trial and error until we arrive at a new construction that does a better job of making sense of things. We change the past only by reinterpreting it, and meet the future halfway by anticipating it. Time travel will produce little benefit for us unless we are prepared to reconstrue what we experience.

Quoting Art48

We choose to watch horror movies not to suffer, but rather to learn from the events of the film from a safe distance in order to gain a measure of mastery over our fears. For most people, what makes their lives rewarding or horrible is closely tied to how they manage to understand and relate to the behavior of people who matter to them over the course of their lives. Our most fundamental sense of who we are is dependent not just on how we see others, but on our reading of how we are seen through the eyes of others. Our choice of schemes of understanding is crucial here. If our framework does a poor job of seeing the world from others perspectives, then we will constantly suffer from anger, alienation, blame and poor self-regard.

Supose you were to go back and become yourself at some earlier point in your life, returning to an earlier point in the block universe. In your description you make this sound as if this would be the you of now, observing the you of then, watching as if at the movies.

Perhaps what you are experiencing now is a "you" of the future, who has "come back" to experience this time...

But that isn't right, since you have no recollections of your future. You are you, now.

And this would be the same for the you of now, re-becoming an earlier you - in that very process you cease to be the you of now.

The "disembodied consciousness... somehow reenter the stream of time and re-experience my life" would not experience that life in any way differently to how you experienced it.

The problem here is the same as that for reincarnation: what is it that is reincarnated? What is it that revisits an earlier time? What could it mean to say that you experience what it is like to be Lincoln? It would be Lincoln experiencing what it is like to be Lincoln. It's not that any disembodied consciousness can experience any portion of any life, since there could be nothing to say that this was Art experiencing Lincoln and not Lincoln experiencing Lincoln.

If you returned to an earlier time, it would not be as an observer, but as that participant; nothing would or could be different.

The philosophical problem for reincarnation - and for the re-embodiment of the OP - is explaining the individuation of the self.

Fair point. My life has largely been free of trouble but I certainly wouldn't want to relive any of it. I choose extinction. :wink:

And the flaw is in taking a concept (in this case, reincarnation) out of its native context.

The Hindus have no problem with any of that. They explain that it is the soul that gets reincarnated; that thoughts, feelings, the body are not the self.

At least for those who still have to work and are at the mercy of employers and clients, the past very much exists.

I was listening to Zizek yesterday in a panel session. He said, 'you can't even control your own erections! How do you think you can control yourself?'

It reminded me of one of the disputes in the early Buddhist orders concerning the status of the arahant, those who were said to have overcome all the cankers and were free of lust, but could still be subject to nocturnal emissions. This was cited by the dissident sect, which was eventually to become the Mah?y?na, as evidence for the fact that the categorisation of arahants was flawed.

How odd. Then it doesn't seem to do what wants.

So some impersonal entity, not me (i.e. not mine-ness), "gets reincarnated"? If that's the case, then I need not care about "the soul" and live as I like (maybe finding a purely immanent, this-worldly basis by which to survive and thrive in the here and now). :fire:

I'm thinking of the the Block Universe as completed, done. And I'm thinking of a disembodied consciousness as having some sense of self. And also as choosing to experience a life (or portion thereof), a life of which every part already exists in the Block Universe. I may sit down and watch a movie and lose myself in the movie, becoming so lost in the drama that I forget I'm just sitting on a couch and watching. The idea is vaguely similar: the disembodied consciousness experiences the movie of a life, but better because the movie is in 3D, and has sound, odors, touch, and taste sensations, too.

Quoting baker

I think the concepts of "soul" and "disembodied consciousness" are similar, if not exactly the same. Choosing to live a life is choosing to experience all that life's physical, emotional, and mental sensations. So, we are in a 3D movie where 3 refers to physical, emotional, and mental sensations. I think that idea is similar to the idea that we are living in a matrix.

A different, perhaps more accurate way to think of the block universe in these terms would be that the you from your past is still there, in an atemporal sense, experiencing the things you experienced.

More broadly, we understand - more or less - what being oneself is in the normal circumstances of growing old, forgetting, being injured and so on. But remove the body and the context in which all this makes sense drops out as well. In philosophical terms, the language game has been over-extended to the point where it needs to be radically rebuilt; we no longer have the capacity to find our way about.

So we make stuff up.

But there is nothing that makes the stuff we make up right or wrong...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myth_of_Er

Yes, this is one possibility. Observers in another time dimension could see our past, but not us in the same time dimension.

The fundamental question, I believe, is of personal identity. One view is that our physical, emotional, and mental sensations being temporary, don't constitute me in the deepest sense. Rather, the more permanent consciousness which is aware of the sensations constitutes my personal identity. Under this view, I (my awareness) would be re-experiencing the current life I'm experiencing.

But there are, of course, other views of personal identity.

What are the minimum requirements for finding our way about? What if I imagine myself as having memory, which includes my history as a body growing up in a conventional world, and the ability to learn. In addition, I have the ability to think but not to perceive an outside world. I am like a writer locked in a room with their private contemplations. Am I then just making stuff up? Is there anything generated within my thinking that can make that thinking right or wrong, that can validate or invalidate my expectations concerning the future directions of my contemplations?

Quoting 180 Proof

I would have thought you're all sufficiently informed about the reincarnation doctrine ...

To recap: A reincarnation doctrine like it can be found in Hinduism teaches that it is the soul that gets reincarnated. The soul is also who a person really is. But when the person is under the influence of maya, in a state of delusion, they don't know who they really are, and mistakenly identify themselves with their body, their mind, their feelings, or in relation to their possessions, their tribe.

Quoting Banno

Not from scratch, though. A person born and raised into a religion that teaches reincarnation will have internalized it even before their critical cognitive faculties have developed. So such a person doesn't actually "make stuff up". Such a person conceives of themselves according to the doctrine of reincarnation: that who they really are is an eternal soul who inhabits a body, and that this body, the thoughts and feelings they have are not who the person really is, nor do they see themselves defined by their possessions, socio-economic status, tribal affiliation etc.

The bigger picture here is that who we think we are (including the abstract concept of what selfhood is) is something we have internalized long ago and take it for granted. Our notions of selfhood are something we become acculturated into even before our critical cognitive faculties have developed.

They can't be, because one is from a religious context (pulling along all the connotations), and the other one is not.

Can one really define oneself?

Your default notions of who you really are are not your own, but inherited from the society/culture you grew up in. So you cannot define your starting point, as that has been done by others already.

At some "personal defining juncture" however you choose to define yourself anew, possibly in contradistinction with your old, inherited idea of "who you really are", that new definition is still going to be in relation to your old one. So it seems that one cannot actually chose one's identity.

Quoting baker

Society is an abstraction, an average derived from individual perspectives. It is true that each perspectival view is shaped and reshaped by its participation in its culture, but this just means that the way I change in response to that constant social exposure maintains its own integrity and uniqueness with respect to the way others within that same culture are changes by their interactions within it. In this way, each of us stand apart from our culture at the same time that we belong to it.

Quoting baker

Just because my new self is defined in reaction against my old self doesnt mean that that new me doesnt comprise its own identity.

So the topic becomes that of individuation - what is it that makes something this and not that? The question applies more broadly than to self, so let's have at it.

Historically there were two approaches. In the Bundle theory, what makes an individual is the bundle of properties that make it up. Change the properties and the identity changes. In the Essences theory, the properties are like pins stuck in a blob of essence. Change the properties and the individual remains the same, that essence.

The idea you both are suggesting is that it's not what one commonly calls one's self that is reincarnated, but a something else, a sort of essence...

But what that is remains undefined, or defined only by hand-waving.

At least since Kripke, there has been a third option, that there need be no essential characteristics of an individual, nor some bundle, but that being an individual is constituted more by the way we treat stuff than by any characteristics the stuff has. Precursors to such a view are also found in both Wittgenstein and the German Phenomenologists.

You can get an idea of what is at play from the SEP article on Relative Identity.

For my purposes here, I don't need to advocate one of these views over the other. Instead I'll just draw attention to the options, and point out that what the two of you are advocating is one choice amongst several, and perhaps not the best one.

comes at the issue from some imagined, internal, solipsistic position. "What are the minimum requirements for finding our way about?" Well, being able to find your way about! As points out, you are already embedded in a community, so much so that your attempts to imagine yourself apart from the world carry the world with them. Basically, Joshs, you can't build the private language you need in order to formulate your solipsism.

Isnt there a fundamental principle in Aristotelian metaphysics that it is the material that constitutes the particular? That the form is universal - Socrates is a man - but his features (or accidents) inhere in the material body. Form and matter. I find that intuitively appealing.

Buddhist views of re-birth are very complex. On the one hand, the early Buddhist texts resolutely deny that there is an individual self that migrates from one life to the next. There are several texts where errant monks are given a thorough dressing down for propagating such nonsense. But then, in Tibetan Buddhism, there is a long tradition of incarnate lamas, who are often identified because theyre able to point to things they owned in their previous incarnation. So what gives? The doctrinal interpretation is that whilst there is no solitary or unified self that migrates life to life, there is a mind-stream (with the musical Sanskrit designation of citta-santana) which continues to manifest life to life. It is sometimes compared allegorically to a fax machine (or used to be, when fax machines were things) - different paper, same information.

It is also said that your state of mind at the moment of death is of paramount importance, as it will influence your destination. (I corresponded briefly with a philosopher whos wife was an East Asian Studies scholar who had written a book on Japanese Pure Land practices for the moment of death.) And there are many possibilities - in the traditional view there are six realms of rebirth (gods, demi-gods, human, animal, ghost and hell realms.) It is widely understood that to suffer a poor rebirth might mean being consigned to the woes of sa?s?ra for aeons of kalpas (and as Carl Sagan knew, Indian astronomy contemplated quite realistic time-scales for the birth and death of cosmic cycles.)

The major difference between Buddhist and Hindu views of rebirth is that the latter believe in ?tman, higher self. That said, the dialectic between Buddhist and Hindu views of re-birth played out over many centuries and there is a vast amount of detail which is impossible to condense into a forum post.

So what.

What Aristotle thought is of some historical interest, but certainly no longer authoritative - I hope. One likes to believe that there has been at least some progress over the millennia.

And much the same goes for that some cultures make up stories about reincarnation. Sure, they might be right.

But you don't actually know. Just-so stories.

You like that stuff. Be my guest, but I'll decline the offer.

Quoting Banno

There can also be a kind of solipsism, or rather, essentialism, built into assumptions about how a community embeds individuals. Thats why I asked about your minimum requirements. Perhaps I should ask what the minimum requirements are to be able to speak of a community. During the period when I am alone writing in my room, I suggest two things are the case. First, I bring to my writing my history as an embedded member of an interpersonal community. Second, over the course of my writing I am capable of thinking beyond the conventions of that history and that community. The language I use to accomplish this is not private because at first it draws from the resources of that remembered community. And as I continue writing I draw from my self, or more properly, community of selves, to transform the sense and vocabulary of my language relative to my starting point. So I draw from both an inter and intra-personal community to produce a language that exceeds cultural conventions, all the while avoiding the solipsism of a self-identical self and the essentialism of a strictly interpersonally defined notion of community.

The stereotypical attitude of modern philosophy is that everything that happened in the past has been superseded by 'progress'. Even if one of its gurus said 'We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all.' And why ask the question if the predictable response is that you don't want to know the answer.

It's a forum discussion about a topic of interest, not a peer-reviewed academic paper. I was going to add, Aristotle and others of that era are 'axial age philosophers'. Much of it is of course archaic due to the historical period in which it was written but it still plays a foundational role in culture. (Although I feel as though your motivation for participating is just to confirm your own views to your own satisfaction.)

Quoting Banno

:up:

Quoting baker

:up:

Anyone like to venture a theory, as distinct from an expression of personal animus, as to why reincarnation is taboo in Western culture?

1. Christian Dominance: Western culture has been heavily influenced by Christianity, which emphasizes a linear progression of the soullife, death, and then either heaven or hell. Reincarnation, which posits multiple lifetimes, contrasts with this view. Reincarnation (strictly speaking, belief in the pre-existence of souls) was anathematised in the 6th century c.e.

2. Cultural Origins: Reincarnation is usually associated with Eastern religions and philosophies, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. Because of this, its viewed as foreign or exotic in Western contexts.

3. Fear of the Unknown: The idea that one could return as a different being in a different circumstance can be unsettling to some people (this dread actually caused a very well known academic in Buddhist Studies, one Paul WIlliams, to abandon Buddhism and convert to the RC Church).

4. Materialism: Modern Western culture relies on science as a guide to what is real. There seems to be no feasible kind of physical or scientifically-understood medium through which memories or experiences can be transmitted life to life.

However, its worth noting that not everyone in the West dismisses or is uncomfortable with the idea of reincarnation. Many individuals and groups do believe in it or are open to the possibility, especially as Eastern philosophies and spiritual practices have gained traction in the West.

What would a 'public specification' comprise?

So, instead of making their own stuff up, they accept and introject the stuff that others have made up; stuff that has been canonized in their culture?

Demonstrating ...

Quoting 180 Proof

There's a few problems, such as -

How is it that old you is the same as young you - directly contradicting Leibniz Law

Chrysippus Paradox

101 Dalmatians

The ball of clay

Theseus' ship

London and Londres

But sure, Aristotle...

Yes. Sure, we're reincarnated; the bits that make up one's body once made up another body. Dig dead people into the compost, use the result to grow carrots so as to ensure theur reincarnation...

Quoting Janus

That is quite close to what seems to have in mind. Eternal recurrence strikes me as rather silly. After all, one doesn't know one is a recurrence, and has no memory of such... it's not as if we will get bored...

Taboo?

Quoting Pew

Seems not.

It seems likely to me that only those who have a firm belief in resurrection would consider the idea of reincarnation somehow "taboo", on account of it being counter to their own dogma. I think it pays to remember in regard to claims for which there can be no evidence that the default would be to simply believe in what is evident; that we simply die and cease to exist.

I think both Spinoza and Epicurus, neither of whom believed in an afterlife, had the most sensible attitudes towards death; simple acceptance and seeing that there is nothing to fear in death itself. Ironically it seems that attachment to the idea of rebirth is an egoic attachment counter to the central idea in the very religions who incorporate it into their system of beliefs.

It seems likely that the idea was incorporated to give motivation to those who are not inclined to think deeply about death.

Spinoza pointed out a similar dynamic with the "carrot and stick" of heaven and hell in Christianity, using desire and fear as motivators to believe.

Source

I know the notion is quite ancient but Nietzsche conceives of 're-experiencing consciously re-living one's exact same life eternally' as a psychological (i.e. conative) thought-experiment, or test, of the degree which one affirmatively lives (i.e. becomes). Existentially, IMO, not a "silly" exercise at all.

I have not found any idea or conception of "soul" (i.e. immortality) in Spinoza. I think you're mistaken, Wayf.

:up:

And Spinoza did not see it as something earned but as being the case, sub specie aetermitatis, for everyone and everything, as I read him. It has been a while since I read the Ethics so it's possible I'm misremembering the details but suffice to say there is nothing at all about rebirth, or concern about anything other than how to live in this world, in Spinoza.

But then, why bother with philosophy? For what reason was Spinoza exiled from the Jewish community? Why undertake the laborious task of composing such complex and lengthy philosophical works, and why read them? Why is not any man in the street equal to the wisest?

I can't see how the secularist reading of Spinoza, just more or less shrug and get on with life, comprehends his obviously spiritual message, the 'intellectual love of God', self-abnegation, the devotion to wisdom, the abandonment of worldly ambitions, which are central in his corpus. He is concerned with inner freedom, freedom of the soul from fear, is he not? That's why I say his philosophy can be compared with Hindu and Buddhist teachings.

After experience had taught me the hollowness and futility of everything that is ordinarily encountered in daily life [ ], I resolved at length to enquire whether there existed a true good [ ] whose discovery and acquisition would afford me a continuous and supreme joy to all eternity. (Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect, para.1)

Spinoza sees the problems of life as arising from the desire for perishable things which can be reduced to these three headings: riches, honour, and sensual pleasure (idem: para.3&9). As these things are perishable, they cannot afford lasting happiness; in fact, they worsen our lot, since craving for them often induces compromising behaviour and their consumption creates useless craving. But love towards a thing eternal and infinite feeds the mind with joy alone, unmixed with any sadness. (Idem: para.10) In the Ethics, Spinoza finds lasting happiness only in the intellectual love of God, which is the mystical, non-dual vision of the single Substance (or Being) underlying the phenomenal realm. The resonance with non-dualism becomes apparent when Spinoza says that the minds intellectual love of God is the very love of God by which God loves himself (Ethics, Part 5, Prop. 36; compare Meister Eckhardt, 'The eye through which I see God is the same eye through which God sees me'.) Since God is the Whole that includes everything, it also includes your love for God, and thus God can be said to love Itself through you. Iff you recognise it!

Quoting Janus

I would not expect Spinoza to have anything to say about reincarnation as it was not part of his cultural milieu, but I provided the passage from Sri Ramana Maharishi to illustrate his view of the matter. As a Hindu, you would expect that he would presume the reality of reincarnation, but he does not.

So I presume that it is for those who 'identify themselves with a body' - I would include myself in that category - that the idea of re-birth at least communicates something important about the human condition.

It's simple; philosophy is about self-knowledge, about understanding the human condition, so as to be able to live the best possible life. He was exiled from the Jewish community for his immanentistic idea of God, his idea that God is Nature, and his denial that both we and God possess free will (Spinoza saw God as necessarily, deterministically acting according to his nature, just as we do).

The "man in the street" may or may not live life thoughtfully. As the saying goes "the unexamined life is not worth living". I don't Spinoza would agree wholly with that, but I think he would certainly say the examined life is better than the unexamined.

Quoting Wayfarer

Spinoza denied that God can love us. The importance of loving God is the importance of loving Nature and loving Life, of accepting it wholeheartedly as it is. " Amor fati". That's why Nietzsche saw Spinoza as a kindred spirit. That's why he says, "the free mean never thinks of death" because the philosopher's concern should only be with this life, not some superstitiously imagined afterlife.

Spinoza advocates complete acceptance, because he was a determinist through and through, from which it follows that all things will be as they will be, necessarily. From this it follows that there is nothing beyond this life to strive for, and within this life only complete understanding and acceptance is worth pursuing. This can be compared to the non-attachment advocated by Buddhism, but none of the otherworldly stuff of the Eastern religions will be found in Spinoza.

Quoting Wayfarer

I don't know where you got the above passage, but it seems to be full of inapt implication and association. Spinoza. like the "this-worldly" Epicureans, saw desire for things "perishable" as being corrosive of equanimity, personal peace of mind, and this is simply a practical realization.

Spinoza understands God or Nature (deus siva natura) as being eternal, and advocates contemplation and love of that nature, and this amounts to loving this life, yet being free of attachment to the temporal things of this life. This is really just commonsense. Spinoza is certainly not a mystic at all; there is nothing otherworldly in him. If we love this life, that amounts to God loving himself ("himself" is misleading here and should really be "itself") or Nature loving itself, but as I said earlier Spinoza stresses that God cannot love us, because God is not a personal conscious being, God is simply Nature being what it is, doing what it by necessity must.

If you want to understand Spinoza you need to actually read him.

Spinoza says philosophy seeks understanding and that our freedom expands as our understanding deepens.

Probably because the very young Spinoza wouldn't keep to himself his critical view that the Torah fundamentally consists of 'superstitious myths' (which years later he expounds on in the masterful Tractatus Theologico-Politicus).

Those who wish to share their understandings wrestle with nontrivial conceptual & existential aporia with other reflective thinkers read and write philosophical texts.

Unlike many philosophers, the "man in the street" simply isn't explicitly aware that he, like "the wisest", often doesn't know that he doesn't know or what he/we cannot know.

Quoting Janus

:up: :up:

To set the record straight, I did a semester on Spinoza's Ethics, and wrote a term paper on it, which was passed. I have forgotten a lot of it, but I don't agree with the secularist reading of it. Spinoza was a mystic. I disagree with both of you on that, and I'll leave it there.

Quoting Wayfarer

And this means what? Not 'seeking union with a transcendent being/reality' (because Spinoza, in effect, argues that 'transcendence' is incoherent, illusory or superstitious).

The Project Gutenberg edition of On the Improvement of the Understanding starts with this paragraph

So how that translates to 'accepting things as they are' escapes me. What is 'a thing eternal an infinite' that 'feeds the mind wholly with joy'? There is a definite sense of turning away from, renouncing, the transitory, and contemplating the eternal.

Quoting 180 Proof

It means abandonment of the transitory and awakening to what is always so, the eternal, beyond the vicissitudes. What is 'ecstatic'? It means 'ex' (outside of) 'stasis' (the normal state). There is the theme of ecstatic union - the fact that he designates it as 'God or nature' does not, in my view, entail that Spinoza was a naturalist in the sense of modern empiricism, restricting knowledge to what can be validated by sensory data. There are books which explore the links between Spinoza, Kabbalistic mysticism and other like sources.

:up:

Quoting Wayfarer

What do you mean by mystic, Wayfarer?

Quoting Wayfarer

Is nature not eternal? Spinoza, as I read him, advocates loving and contemplating the eternal aspects of nature. For example, we don't understand a tree to be eternal, but transitory, but it is not as transitory as a passing breeze, and yet both are eternal aspects or possibilities of nature. What do we love about the tree? We love it's beauty, its livingness, no? Beauty and livingness are eternal, and we find them everywhere..

Quoting Wayfarer

Spinoza is usually classed as a rationalist, and he did believe in the power of intellectual intuition. On the other hand, he saw all otherworldliness as superstition, as an illusion to be seen through, and this is simply undeniable.

Definitely not. Everything in nature, every natural phenomenon, is transitory and subject to decay. Nowadays nature as worshipped as a stand-in for 'the unconditioned' but that is because our culture has systematically destroyed any real metaphysic of the unconditioned.

I provided my definition of the mystical above.

Things, beings, entities are not eternal, but nature itself is. Spinoza drew a distinction between natura naturata and natura naturans. The former is created nature, transient nature and the latter is the eternal active creative power which brings about created nature.

Quoting Wayfarer

I guess you might call Spinoza a "natural mystic', but there is nothing transcendent of supernatural in his philosophy; if you think there is then you simply don't understand his philosophy, and if you want to remedy that I would suggest reading his actual works.

What is the point of quoting Maritain in a discussion about Spinoza? The two could not be further apart, Maritain being the apologist for Catholicism that he was.

Natura naturans - the divine, infinite substance that continuously brings about and sustains the existence of natura naturata. It is the underlying, unchanging source of everything in the world.

In Spinoza's philosophy, these concepts are essential components of his monism, where everything is ultimately one substance (God or Nature) with two different aspects. Natura naturata represents the changing, finite world of effects, while natura naturans represents the unchanging, infinite cause or source of those effects. Although here I have difficulty with the use of the word 'substance', as it's too easy to interpret as being a kind of material substrate. In Spinoza's philosophy, "substantia" refers to a singular, infinite, and self-sustaining reality that encompasses all of existence. It is more akin to what we might call "reality" or "the ground of being" rather than the everyday sense of "substance" as a physical or material thing. (I cant see how it is, for instance, compatible with contemporary scientific naturalism.)

I learned about a current title on Spinoza, 'Spinoza's Religion', by Claire Carlisle, which I've started on. From one of the Amazon reviews of that book:

I've read the intro and just now shelled for the remainder.

Quoting Janus

The point is, not who Jacques Maritain is, or the fact that he's Catholic, but what it says about nature and naturalism.

I told you, I have studied Ethics, at university level, a long time ago, but I know full well how easy it is to transgress the anti-religious taboo that exists on this forum, so I guess I'll just have to live with that, somehow.

Quoting Wayfarer

Proof you've not read (or understood) Spinoza's Ethics, esp. section I "Of God". qed.

Quoting Janus

:100: :fire:

As @Janus was first to point out, sir, you clearly do not understand what Spinoza says quite clearly in his Ethics. :kiss:

Quoting Banno

This just illustrates what happens when one takes a concept out of its native context and tries to understand it and work with it regardless of said context. It's nonsense, and a waste of time.

To be clear, I'm not "advocating for reincarnation". In a broad sense, I'm advocating for semantic holism.

It cannot be said that what children do when they internalize the religious teachings of their parents and their community is an act of "choice" or conscious acceptance. Given that for children born and raised into a religion the exposure to religious teachings begins to take place even before the child's critical cognitive abilities have formed to the point of consciously being able to a make choices, to consciously accept or reject things, it's remiss to say that this is what is happening.

It's like with one's native language: it's not subject to one's choice, it "just happens".

Religious doctrines, in order to "make sense" to a person, need to be internalized early on in life, or perhaps can be assimilated later only if the person is undergoing a psychologically intense period in their life.

It's not clear that it is possible to accept and internalize any doctrine/teaching/philosophy/ideology simply by reading a syllogism.

You know it's more complex than that.

What is the case for you isn't necessarily the case for everyone else. Your case doesn't prove anything much about the general pattern (which is what I'm talking about).

I suppose externalizing like that can be really helpful.

But there are more ways to gain distance from something religious/spiritual other than declaring it nonsense.

I maintain that my way of distancing is less confrontational; certainly not as egoically aggressive and satisfying as declaring something religious/spiritual to be "nonsense". I like my way, it makes the religious/spiritual problem into a non-issue. It makes it into an "other people's problem".

Lack of diplomacy and lack of pragmatical insight on his part.

Autonomy.

I've been unable to see any such advocation. Perhaps if you were to set it out more explicitly, I'd be able to follow.

But especially in virtue of adopting semantic holism, it seems reasonable to ask what it is that is reincarnated; the answer will after all tell us where reincarnation fits in any mooted semantic web.

Quoting baker

Yep.

Quoting baker

Well, sure. There's all the living, doing, wanting, making that takes place within the made-up world. Unfortunately including sacred cows and the existence of the dalet. If we are to treat Hinduism holistically, such must also be taken into account.

Quoting baker

Interesting. There's a tension between placing emphasis on autonomy while maintaining that one is culturally embedded, as you did in your reply to Joshs, .

No, I mean individuation, not autonomy, and am looking to the logic of the description of reincarnation and asking, again, what it is that is born again. And it seems that we not only do not know, but have no way of determining the answer; and so we turn to mandating that it is so, instead. We make it up.

Im a bit unclear as to why this question keeps being asked. The studies of children recalling past lives observe that children are born who apparently remember details of their past lives - where they lived, their names, parents names, and so on, details which were then cross-checked against documentary and other evidence. There were also numerous cases where physical deformities and birthmarks corresponding to sites of past-life trauma were observed. So the answer to what is born is a child with past life memories and sometimes physical marks. Doesnt that answer the question?

It's tempting to treat this as a curious piece of biography, and leave it. But.

Your suggestion is that it is memory that is reincarnated; @Baker says otherwise. There is a discrepancy amongst the advocates of reincarnation. My evil purposes can be served by niggling at that. The vast mass of humanity have no such recollections, so one might conclude that if that is what reincarnation is, it is very rare indeed. From a more philosophical perspective, it is just not clear what it is that makes you the reincarnation of Napoleon, or whomever...

At issue is the capacity of advocates of reincarnation to present a coherent account.

Reincarnation involves something moving from one body to the next - being clear as to the nature of that something is central. And problematic.

Thats the issue - a medium by which memory and experience is transmitted. (Incidentally I also noted that the one book I read on it shows that most of the remembered previous lives are not of Napoleon or Julius Caesar but ordinary people with unremarkable lives.)

And what it means for an experience to be reincarnated is obscure. Are you the experience of being a handmaid to Cleopatra? And this despite having no such memory?

We have a congenital difference, you and I, that leads me to think of you as credulous. I won't be able to show you - it's not just that the evidence is insufficient, but that it is incoherent.

My appologies, .

Quoting IEP Immortality

Quoting Stephen Nadler

Quoting Wayfarer

Spinoza said the free person thinks least of all death, he says nothing about fearing death or the afterlife.

From here

Socrates presents the problem arithmetically in the Phaedo.

The overarching question of the dialogue is what will happen to Socrates when he dies. The concern is that the unity that is Socrates will be destroyed. In order to address this Socrates divides his unity into a duality, body and soul. It is by this division of one into two that he attempts to demonstrate his unity in death. If each is one then Socrates is two. But since he is neither the one (body) or the other (soul) then the two together must be a third.

How can there to be a logos or an account without a proper count? Is Socrates one thing or two or some third thing that arises from the unity of these two separate things?

For my part, I suspect that individuation is an act rather than an observation. I might borrow Searle's counts as here: we can choose what we like to count as an individual. Then it's the utility and community acceptance of the mooted usage that carries weight. Or something like that.

I'm familiar with the efforts to debunk Stevenson, but many of them clearly have their own agenda.

The background to Stevenson's research was that a chair was endowed at the University of Virginia by Chester Carlson, who had made his fortune by inventing xerography. His wife was a Theosophist with interest in spiritual philosophy (they also helped fund one of the early Zen centers.) Stevenson occupied that chair for around 30 years and during that time documented thousands of cases. (The same department at the University of Virginia - the Division of Perceptual Studies - has become a world-leading 'centre for woo'. Later books including Irreducible Mind and Beyond Physicalism.)

I've read the Wikipedia entry on Stevenson, but again, I think there's something of a bias on Wikipedia against the paranormal (and I say this as a Wikipedia contributor and subscriber). There's a well-known group Guerilla Sceptics who make it their business to throw shade at entries on the paranormal (they were heavily involved in the controversy over Rupert Sheldrake's deleted TED talks.) Consequently a reading of the Wikipedia article leads to the view that Stevenson's entire corpus can be dismisses as 'shoddy research', but having read some alternative accounts, I don't necessarily buy that conclusion.

Quoting Fooloso4

Perhaps an analogy can be drawn by comparision with the way stem cells individuate in the growth of the embroyo. Any developing embroyo comprises hundreds of millions of separate cells, yet as development occurs, the individual cells are all integrated into a single organism. Similarly a human person comprises many separate parts that nevertheless possess functional unity. There seems to be such a holistic principle at work on many levels, biological and psychological. I think that at least deflates the question of 'how many Socrates there are'. //I think that squares with the ancient idea of the soul as 'the principle of unity' as distinct from 'an entity'.//

Thanks for that, but I've decided not to try and assimilate Spinoza again. The Ethics reads like a 250 page insurance contract. After yesterday's conversation I did rather impulsively buy the kindle edition of the Claire Carlisle book Spinoza's Religion so will persist with reading that.

Right, I haven't said the child necessarily has any choice in what is accepted and introjected. I used the word "accepted" but that was not meant to suggest that the child necessarily had any choice in that acceptance, certainly not any choice in any libertarian-freewill or rationally chosen sense. But I would hesitate to claim that all children must acquiesce to what they are being taught. Humans are diverse.

Language does not strike me as a good analogy since it is a tool not a belief; one does not accept or reject it but rather one learns to use it.

As you know I am not against people believing in rebirth or whatever. Obviously there can be no definitve evidence either way. What I am curious about is why people care about it, since it obviously cannot be understood to personal survival of death. Is it an irrational fear of annihilation?

It seems to me that whatever the truth might be regarding rebirth, the most important thing is living the best life in terms of acceptance and love of oneself and others, equanimity and non-attachment to inconsequentials that we can. Worrying about what happens after death does not seem to be conducive or relevant to that task.

I have my reasons, and I started writing them out, but it's a bit personal. Suffice to say that I don't believe birth is an absolute beginning, or death an absolute end; a life overflows those bookends. And I think annihilation is considerably less frightening than the alternatives - it's comforting, in a way, because it zeroes out anything you might have done in your life. I mean, if you're a mass-shooter who kills a number of people then yourself, you would presumably believe that that act ends it all. If it turns out not to, then....

During Buddhist Studies, I studied the longest sutta in the early Buddhist texts, 'the Net of Views'. It describes all the various views considered to be fallacious by the Buddha. About half are 'eternalist' views - theories about continuing to exist in future lives. The other half are nihilistic views, that death is an absolute end and that human life arises as a consequence of chance. The translator, Bhikkhu Bodhi, remarked that this kind of view is characteristic of modern culture, something which is believed to be 'proven by science'. Ultimately, both views (or dispositions) derive from either the desire to continue to be (eternalism) or the desire not to exist (nihilism. In other words, they're motivated by either greed or aversion. Although this is drastically condensed and the text itself is long and detailed.)

I'm considering the idea - I've discussed this with Schopenhauer1 - that we're condemned to existence, in one realm or another. We don't get a choice about it because we haven't understood what is the causal factor behind all of it. So 'ending it all' would not, actually, 'end it all'. I suppose that is the Buddhist view in a nutshell, not that I want to claim any special insight into that or mastery of it.

The flipside is the idea that everything you have learned throughout your life will die with you, apart from what you may have imparted to others or committed to writing, music or artwork. But then what value can any life lesson be but within life itself? Also, personal rebirth is not necessary to support the possibility that everything which is done and learned is somehow "recorded' as is conceived in the idea of the akashic records (which is not to say I believe in that either)

Spinoza was a strict determinist; he believed free will is an illusion based on the illusion of our separation from the cosmos. If this is right, then everything everyone does is a manifestation of the "will", of the inevitable unfolding of the cosmic process. Apropos this Kastrup also holds that free will is an illusion.

But the other point against the idea of rebirth, or at least against the idea that it could be a rationally motivating consideration for us, is that whatever suffering might be coming to the entity that is the reborn you on account of ill deeds done by you, that could, rationally speaking, have no more significance for you than the suffering of any being, past, present or future, given that this future 'you' will have no conscious connection with the present you whatsoever. So, if we are going to care about, and act to ameliorate the suffering of any beings it makes more sense, rationally speaking, to dedicate oneself to ameliorating the suffering of beings that we know exist and that we know are suffering.

Quoting Wayfarer

This makes no sense to me; I would love to live forever provided I am healthy and not suffering too much pain. But I am more inclined to believe that my personal self will end at death and that the constituents that make up what I am will continue on in other forms for as long as the universe exists. My reason for not believing in any form of personal rebirth or afterlife is not that there is any definitive evidence against it, but simply that I cannot make rational sense of the idea, and I cannot believe something I am incapable of even making coherent to myself. So, I can honestly say that my thoughts on this are not at all driven by wishful thinking.

Yep.

I get that. I cant make rational sense of the obverse, although Id never seek to persuade you or anyone else.

Quoting Janus

Not according to this article

:up: :up:

Quoting Janus

But that being will nevertheless be the subject of experience, a conscious agent.

One of the minor epiphanies that struck me was when I studied prehistoric anthropology. I suddenly had a sense of how long our ancestors had lived for those many thousands of generations, often under painful and harsh conditions, obviously with no modern medicine or life comforts. I realised one day, those people were me - me with my struggles, joys, children, and the rest. Obviously Ill never know who they are - I know my family tree back to the mid 1800s - but its not hard to imagine that they were men just like myself, carrying the torch, so to speak. (I started to wonder if this is where ancestor worship originated.)

Similarly, that when I was born into this life, I did not (contra Locke) arrive a tabula rasa. I inherited many characteristics, I was born into a situation, and I also embody various archetypes and proclivities, which have shaped the life Ive lived in the (now) 70 years since. When I die, and thats obviously not that far off any more, therell be one child born to carry on.

You are mistaking determinism for fatalism. On determinism your mind can change in response to events. The way things are determined is ongoing and there is no reason to think that events occurring in philosophical dialogs can't change our minds.

https://www.naturalism.org/philosophy/free-will/fatalism/determinism-vs-fatalism

I added a link just before your post showed up. It's a very brief discussion of the differences.

Socrates is this guy they know and love. This person they talk to and see engaged in conversation in the marketplace. What will happen to him when he dies?

It is easy to miss what Plato is up to here. The argument moves in two opposite directions.

The common assumption is that Socrates is attempting to persuade his friends that the soul is immortal. He thinks that for many such a belief is beneficial.

The philosopher, however, seeks the truth of the matter, to the extent that is possible. The second possibility of what happens to us when we dies is raised explicitly in the Apology, but here, as he is about to die, we must, so to speak, do the math. Rather than myths of rewards and punishment and reincarnation, we are confronted by the incoherence that arises when a single, unified person is divided in two and only one part of who he is is believed to endure.

I don't really seek to persuade either but to present and be presented with rational arguments for beliefs and standpoints, since this is a philosophy forum and I think that activity of presenting and being presented with (hopefully) rational argument is what the critical activity of philosophy is all about.

There are things I believe or at least tend to entertain that I would not try to argue for, because I realize they are merely personal articles of faith.

Quoting Wayfarer

I don't think he is asserting the truth of the libertarian conception of free will. From the article you linked:

And from the horse's mouth:

:100:

I don't know what the significance of 'libertarian' free will is, and I recognise that the will is constrained. Kastrup says he's not for either determinism or libetarian free will, that it's a false dichotomy. From that video 'nothing in the universe knows what our pre-determined choices are going to be'. 'The universe plays itself out in our actions' - much like something Alan Watts used to say.

I think the subtle issue behind this is the question of ego. If Krishnamurti was asked whether we have free will, he would always respond that 'will is the instrument of desire'. His teaching was always 'choiceless awareness' - to see what it is that drives our likes and dislikes as they are. The will itself is not free, because it's always conditioned. But I don't think he would accept the kind of deteminism that naturalists posit either. He represents the kind of liberation which is not within the ambit of Western philosophy generally.

Quoting wonderer1

From which

I think the subtle issue there is 'what does "outside" mean?' Does it mean, 'outside what we currently understand as natural causation?' Because, as per Hempel's dilemma, our understanding of what constitutes physical causation is constantly changing. What I object to with determinism as usually presented is, 'hey we (scientists) know what the real causes of everything is, and your sense of rational autonomy is illusory.' That's where it becomes scientistic rather than scientific - everything has to be explainable within the procrustean bed of physical causation.

Besides, determinism has been called into question since the discovery of quantum mechanics. Ernst Cassirer (neo-Kantian philosopher) argued that quantum mechanics did not necessarily negate determinism but instead revealed a new form of determinism that was based on probabilities and statistical laws. He saw the probabilistic nature of quantum events as a different kind of determinism, one that operated on the level of statistical regularities rather than strict, deterministic causation.

While C S Peirce's tychism predated quantum mechanics, it shares a philosophical affinity with the probabilistic and indeterministic aspects of quantum theory. Both tychism and quantum mechanics challenge the classical, deterministic worldview by acknowledging the presence of randomness and probability in the description of natural phenomena.

I also see a conflict between determinism and rational causation - that as rational agents, we are able to make decisions that can't be reduced to physical causation. (cf 'the space of reasons'.)

Kastrup is asked 'is there randomness involved' and responds 'I don't think so, I think it's the word we use when WE don't know'. He says that if we did know all the factors involved, determinism would be maintained, but that it's computationally irreducible to derive the details of the causal chain.

God works in mysterious ways!

Anyway this has drifted a long way off topic (although it is a kind of omnibus topic) but thanks to both for those resources.

That might need reworking, but I gather you are asking about what happens at the point of death. The language "divided in two" is loaded with dualism. The common prejudice is that at death something leaves the body. I don't think that's right - rather the body stops doing stuff it once did. It no longer works in the same way.

That can be put in terms of identity. The body no longer serves to present the characteristics that made it the person it once was. In the same way one looks at a person in pain and understands that they are in pain, one understands by looking at a corpse that it no longer functions as a person.

Yes, there is a sense in which we, as a more or less self-determining organism. determine our own actions, but those actions are determined by processes we cannot be conscious of. And we are not really separate from the rest of nature and its constant unfolding.

Libertarian free will presupposes a radically free soul, so it is a necessarily dualistic conception subject to the incomprehensibility of interaction.

A libertarian is simply one who rejects compatibilism and determinism. The specific varieties differ. According to SEP a libertarian is simply one who requires "that ones action not be causally determined by factors beyond ones control" (link).

Who really says anything remotely like that? You seem to enjoy posting quotes from people who you see as supporting your view. Why resort to a straw man in the case of views you disagree with? It comes across to me as anti-physicalist propagandizing. Why don't you provide quotes, of actual statements made by the people whose views you oppose, rather than put words in the mouth of a figment of your imagination?

Quoting Wayfarer

I generally see people's use of "scientistic" as indicative of an anti-science bias on their part. Anyway, you are putting up a strawman again, and trying to paint physicalists with views they do not hold.

The simple fact is that you haven't considered physicalism in a charitable way, and so don't know what it is like to look at things from a physicalist perspective. It's not that "everything has to be explainable within the procrustean bed of physical causation." It that those who seriously study the causation of things, find through life experience that explanations that don't conform to the Procrustean bed, never seem to yield reliable predictions.

Science is enforced humility:

You don't understand the perspective, because you simply don't have the life experience required to have developed such a perspective. By all means, demonstrate something that doesn't fit the Procrustean bed, but I'm not going to hold my breath, nor spend a lot of time addressing quotes of the sort you like to post in the meantime.

But does anyone disagree and claim that the body keeps working the same way after death? An appeal to a soul is an appeal to a reason why a body "stops doing stuff it once did." Plato would not have been surprised to hear that dead bodies act differently than live bodies.

(I realize this is all quite far from the point that @Fooloso4 was trying to make.)

Quoting Banno

Well, the interesting thing is that it cannot be put in terms of identity, because the identity of the body comes from the fact that it is a unified organism. Once it dies it is no longer a unity, and it is therefore no longer one thing, possessing a single identity. It will quickly decompose into a million different parts. The disintegration occurs because the "soul" (unifying principle of life) is no longer enlivening the body.

Just for fun I should add that a substantial change takes place at death, an essential corruption. When a human dies the human no longer exists, and only the corpse remains, where the human and the corpse are two fundamentally different kinds of things. Whatever "grandpa" was, he is most definitely not the thing in the casket. It is inadequate to say, "Grandpa is now functioning differently."

The site you provided - which is a very well-presented and well argued site - says 'nature is enough'. And as the site is devoted to naturalism, then it rejects what it says can be categorised as 'supernatural', the implication being that the natural sciences are a superior source of insight to religious beliefs or philosophies. Other examples:

He's arguing, there is no superior source of insight to science. So that is more than 'remotely like that'; it is actually that.

I quite agree that the natural sciences are indispensable across a huge range of applications, and within certain ranges are universal - but not all questions considered by philosophy are amenable to scientific or naturalistic explanation. That is particularly so in the case of ethics and philosophy of mind. Again, that site has a very rich array of arguments in support of a kind of naturalist compatibilism. But the central thesis that humans are natural beings, devoid any faculty or attribute which can be understood as transcending nature, is itself based on a methodological assumption, which then is treated as a philosophical axiom. And that is mostly framed in the context of the perceived tension or conflict in religion vs science, the subject of a sub-section on the site, Naturalism Vs Theology.

Quoting wonderer1

I understand it perfectly well, thank you, and in its context it is completely unexceptionable. Nothing to do with my criticism of physicalism.

I had the idea - please correct me if I'm wrong - that in the Aristotelian tradition, 'the soul' is seen as something more like an organising principle, than a ghostly entity. That is what is meant by 'the soul is the form of the body', isn't it? I think there has been a tendency to reify that into a literal 'thinking thing' from which the issue arises of its separability from the body.

No. You are simply reading your preconceptions into the quotes you posted.

Yep, that's his usually m.o.

Wonderer1 asked

Quoting wonderer1

I did exactly that, and also presented some arguments as to why I differed with them, apparently to no avail. (Although I do recognise that piggybacking comments with gratuitous jibes directed at those you disagree with is part of your usual MO.)

i don't think I said or implied otherwise. I was questioning the phrasingQuoting Fooloso4

I don't think you are on the same page.

The question is perhaps as old as man.

Quoting Banno

It reflects the dualism that Socrates is responding to. Then as now the division of body and soul was common. As you say:

Quoting Banno

He uses the division of body and soul, and in doing so brings that belief into question.

Quoting Banno

That was observed. The question or questions, however, remain - what happens to the person? Socrates entertains two possibilities in the Apology -

1) The continued existence of the soul separate from the body

2) Oblivion. An endless, dreamless sleep.

In the Phaedo, however, he is silent about the second possibility. He does not state it explicitly, but the common assumption that underlies the first proves to be its own undoing. Socrates is not simply a soul attached for a time to some body. Socrates is a whole, a living being, that soon will no longer be alive. Soon Socrates will no longer be.

Notice how I talk about not taking concepts out of their native contexts?

Of course.

In contrast, ask yourself why you want to even think about reicarnation at all.

I am well aware of this tension. I actually keeps me up at night.

Quoting Banno

Indeed, and as the doctrine of reincarnation says, this is because most people are under the influence of maya, illusion, where they don't know who they really are.

To be clear, I'm not using Stevenson's work as some kind of evidence for reincarnation. In fact, I think it's misleading, I dismiss it. I think it's irrelevant to what Hinduism and Buddhism teach on reincarnation/rebirth.

Quoting IEP Immortality

That's a good example of what happens when a concept is taken out of its native context.

In Hindu and Buddhist teachings, the "number problem" is addressed thusly:

a living being is reincarnated/reborn

1. across various species (sometimes as a human, other times as an animal, yet other times as a deity, etc.)

2. also sometimes on other planets, not just on Earth.

I don't believe in any form of afterlife (such as in Christianity or Islam), not in reincarnation, not in rebirth.

Yet I know enough about them that they all make sense to me.

I surmise that the reasons why I don't believe in any of them are:

1. Given that I am familiar enough with several afterlife/reincarnation/rebirth doctrines to the point that they all make sense to me, they very fact that this is so makes it impossible to prefer one over the other. They can't all be right, but how could one choose?

2. Conceptually, afterlife/reincarnation/rebirth doctrines (and religions in general, as a whole) are about things that precede me or contextualize me. Choosing one would be like attempting to choose my parents or the land where I was born. It's an unintelligible, impossible choice.

3. I am not a member of any religious community. I think that if I would be, this would change things for me entirely.

Quoting Janus

I think that most people who believe in reincarnation/rebirth don't believe it on account of "evidence". Most of those believers were simply raised into such religions, so it's never been an active issue for them. But I also know Buddhists, some of them even monks of many years, who use Stevenson's work as a basis for their belief in rebirth (which is actually very un-Buddhist).

I think it has to do with a nagging concern that can be summed up as "Is this all there is to life?"

The unsatisfactoriness and fleetingness of life makes them wish for something more.

Then there is also the question of justice. If one lifetime is all there is, then how can it be fair that some children die of cancer, while some criminals get to live long, happy lives. And if we are to accpet that life isn't fair, then what does this mean for our sense of morality? The topic of this thread is also "the problem of evil".

Some children acquiesce and some don't. Not all children are equally well acculturated into the religion they are born to and raised in. For some, it's a traumatic experience (like being beaten by their religious parents and teachers), for some others, it's apparently a fairly joyous one. Families and communities are different and have various approaches to the teachings (esp. in terms of which teachings they emphasize more and in the context of what particular family and social dynamics etc.). (I've known Christians who are apparently really happy about the Gospel. I think that's bizarre. I've no idea how the do it.)

I think it's similar with religious doctrines. They function as cognitive tools. The point of religious belief isn't merely to hold it, but to do something with it, to have it inform one's thoughts, words, and deeds.

You're so confident that you're going to get a human rebirth??

It's similar with the way atheists of the Dawkins type don't believe in God. Their atheism is an atheism of a god that no actual theist believes in. Not because Dawkins' idea of god would be a strawman, but because it's something so abstract and so general that it doesn't match any existing theistic religion.

Similarly, the kind of disbelief in reincarnation some are displaying here is a disbelief in a notion of reincarnation that no believer in reincarnation believes in. In this case, these disbelievers' notion of reincarnation is partly a strawman, but mostly it's just based on ignorance of actual reincarnation doctrines.

I think that's basically right, but it does get complicated. Speaking plainly, for the Aristotelian the soul is the principle that accounts for the difference between a living body and a corpse. It is the principle of life of a living body, and this includes human, animal, and plant bodies.

The question of separability arises only with rational souls (human souls), and I would have to review the strictly Aristotelian literature on that topic. My guess is that some Aristotelians accept separability and some reject it, but a common point would be that if separated souls exist they are not wholes, but rather parts (i.e. the body is an intrinsic part of the human being, and not a mere appendage).

Here is what you said:

Quoting Banno

The idea is, "Rather than something leaving the body, the body stops doing stuff it once did." Hence my <post>, noting the false dichotomy.

A similar faux pas would be, "Rather than the engine driving the car, the wheels make it move." Those who claim that the engine drives a car do not deny that the wheels make it move, and therefore such a claim is an ignoratio elenchi.

Quoting Janus

The unspoken assumptions in many of these discussion are that "a particular claim is being proposed for discussion" or "a particular claim is being proposed for belief".

In my experience, this is not how religious/spiritual people think or approach discussion of religious/spiritual topics.

For example, for traditional Hindus, an outsider talking about reincarnation would be perceived as an idle intruder, someone who is thinking and talking about things they have no business talking about, being an outsider (although it would take the Hindus quite a bit to actually say so). In traditional Hinduism, religious conversion is an unintelligible concept. For them, religion is something one is born into, like caste, and not something subject to choice.

I find that for many traditionally religious people, religious doctrines are something one either believes or doesn't believe, not something that would be subject to empirical study or experience. Those religious people who proselytize will sometimes offer some "reasons for belief", but at least some of them will also say that those reasons are just provisional, a "tool to help the unbelievers", and not actual justifications for the religious claims (for those claims are not viewed as needing justification at all).

There is a pretty huge spectrum on that matter. Here in the US there is no shortage of Christians who believe that people should have Christian beliefs.

LINK

This sort of rhetoric appeals to a high percentage of US Christians.

Oh, yes. How you square this with semantic holism remains unexplained.

Quoting Fooloso4

I'll take your word for it, although I recall reading a similar account elsewhere, with Plato writing differing accounts for various audiences. What's curious is the way in which talk of division or of a spirit leaving the body comes so easily.

I want to draw attention to what is a visceral difference between how one sees a living and a dead body.

We brace ourselves against this with ritual, seeking some sort of continuity or normality. But our grief recognises the loss.

I am familiar with them too, but I can't say they make sense to me beyond the fact that they are all logically possible in the sense of not being obviously self-contradictory. That said, I think the Buddhist concept on the face of it is the most incoherent. The Hindu notion of a reincarnating soul seems at first glance to make more sense to me, although that opens up all the problems associated with dualism. Resurrection is another can of worms because it involves positing an omnipotent God.

Quoting baker

I agree with this and often say that critical discussion has no place in the contexts of spiritual disciplines and religious practices, and even, as Hadot notes in the kinds of ancient philosophies which consisted of systems of metaphysical ideas meant to support "spiritual exercises". But tell that to the fundamentalists!

In any case, this is a philosophy forum where ideas and arguments are presented for critique, so if people want to present their beliefs and ideas here, they should expect questioning, criticism and disagreement.

I think the interesting philosophical question is that the most common reaction to Stevenson's research is that it couldn't be true, that there must be something wrong with him or his methodology, and that it can or should be ignored.

Quoting baker