Reflections on Thomism, Kierkegaard, and Orthodoxy: New Testament Christianity

I'd like to discuss this topic in 3 parts. The first is dedicated to the legacy of Thomism in the modern world according to two very different interpretations: One centered on the work of Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, a "Strict Observance" Thomist, and the other centered around the Lublin School of Thomism at the Catholic University of Lublin in Poland. I will compare the two and argue why Lublin Thomism, or "Polish Existential Thomism," has risen in popularity since John Paul II's era. The second part of this post will be dedicated to unraveling why Soren Kierkegaard is possibly one of the most important Protestant theologians to have ever lived and discuss his impact on non-Protestants. The third and final part will discuss how these positions are similar to Orthodox Christianity and ultimately conclude with what Catholic and Protestant thought are lacking in and that is an emphasis on mystical theology.

The "Strict Observance" Thomism of Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange and the Phenomenological-Existential Method of the Lublin School

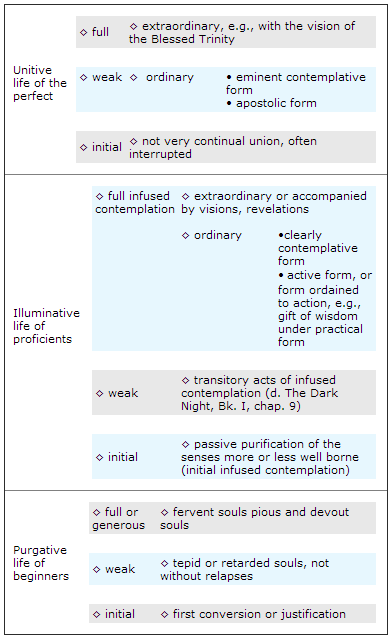

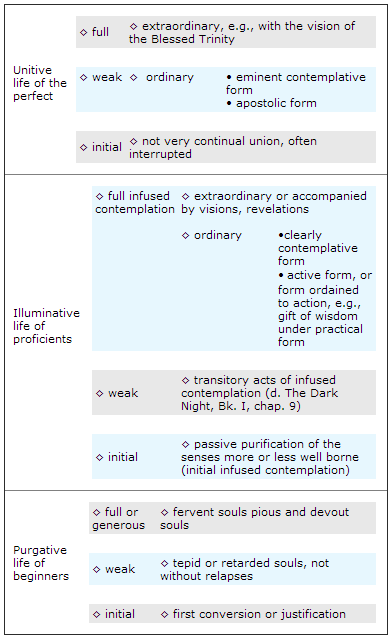

I tend to downplay Fr. Garrigou-Lagrange for a number of reasons. Firstly, Strict Observance Thomism is a hard, often literalist, reading of the Corpus Thomisticum, the works of St. Thomas Aquinas. Garrigou-Lagrange saw Thomism as a true "theory of everything" that could solve every problem imaginable; I generally don't like this approach because it is too limiting intellectually. However, his legacy of work is astonishing. His commentaries on the Summa Theologica are unbelievably insightful (The One God, Christ the Savior). His magnum opus which as influenced me greatly is his book The Three Ways of the Spiritual Life, published initially as The Three Ages of the Interior Life. Garrigou-Lagrange touches on a mystical theology, drawn from people like St. Augustine and St. John of the Cross. This diagram found in his book, to be read from the bottom up, is helpful in understanding his mysticism -

This follows the classic patristic model of purgation of the self (kenosis), illumination of the self (theoria), and the eventual divinization or sanctification of the self unto God (theosis). This classical paradigm has influenced just about every Christian intellectual, be it western or eastern. The Lublin School agrees with this format but differs in terms of methodology. While Garrigou-Lagrange read Aquinas as "hard" as he possibly could, Lublin Thomism seeks to use the philosophies of phenomenology and existentialism to better understand the human experience in terms of faith. Notable thinkers here are Mieczys?aw Albert Kr?piec, who is considered the founding figure of the Lublin School, and Karol Wojty?a, known to the world as John Paul II; This school of thought was found as a reaction to the rise of the Polish Communist Party and was seen as an attempt to combat Marxism. The major difference between a Garrigou-Lagrange and the Lublin Thomist's is the emphasis on personalism, a modern philosophy that asserts that the human person is a free responsible moral agent made in the image of God; Garrigou-Lagrange was almost always critical of modern philosophies. I think we should take Garrigou-Lagrange to heart; The outline of his mysticism is wonderful and very practical. However, the personalistic stance of Lublin Thomism is much more applicable to questions about everyday life.

The Impact of Kierkegaardian Existential Theology

Soren Kierkegaard is known to history as a melancholy Dane but a bright intellectual; John Paul II was known to have been an admirer of Kierkegaard, as his thought meshes well with Lublin Thomism. To breakdown his thought, man lives in a state of despair which is sin. When confronted with two moral extremes we experience anxiety, which according to him is our ability to feel total freedom. The aesthetic life is a life guided by pleasure; We rarely take into the account the consequences of our actions. The ethical life is a life guided by rational inquiry into what we do and say. This ultimately is followed by the religious life, taking a "leap of faith" into the hands of the Unknowable God. Jesus Christ is considered by Kierkegaard the ultimate paradox because of the idea that Christ is the God-Man, the connection between the physical and the spiritual. Kierkegaard meshes well with the Lublin School because of their focus on human experience while not falling into relativism. Kierkegaard constantly spoke of Christendom being without Christians because he felt many of the established churches fell short from "New Testament Christianity."

Holy Orthodoxy as an expression of New Testament Christianity

This leads me to discuss the spirituality and praxis of the Eastern Church. Orthodoxy is an ancient tradition that is older than the Tridentine Mass and Protestant services based upon that. The Divine Liturgies of the various Orthodox Churches as well as Eastern Catholic Churches have a much older feel. Culturally these churches do not like change at all. The practice of hesychasm, contemplative prayer using the Jesus Prayer ("Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner"), is the heart of Orthodox praxis. This practice grounded in the intellectual tradition of Palamism, the thought of St. Gregory Palamas, is a gateway into a mysticism that is not only practical but an expression of New Testament Christianity. Roman Catholics and Protestants don't need to do away with their traditions in order to integrate this into their spiritual life; The format of hesychasm follows the patristic model of mysticism that Fr. Garrigou-Lagrange attempts to model. In conclusion, the legacies of these great intellectual and theological traditions provide a route to unravel what New Testament Christianity really is all about.

The "Strict Observance" Thomism of Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange and the Phenomenological-Existential Method of the Lublin School

I tend to downplay Fr. Garrigou-Lagrange for a number of reasons. Firstly, Strict Observance Thomism is a hard, often literalist, reading of the Corpus Thomisticum, the works of St. Thomas Aquinas. Garrigou-Lagrange saw Thomism as a true "theory of everything" that could solve every problem imaginable; I generally don't like this approach because it is too limiting intellectually. However, his legacy of work is astonishing. His commentaries on the Summa Theologica are unbelievably insightful (The One God, Christ the Savior). His magnum opus which as influenced me greatly is his book The Three Ways of the Spiritual Life, published initially as The Three Ages of the Interior Life. Garrigou-Lagrange touches on a mystical theology, drawn from people like St. Augustine and St. John of the Cross. This diagram found in his book, to be read from the bottom up, is helpful in understanding his mysticism -

This follows the classic patristic model of purgation of the self (kenosis), illumination of the self (theoria), and the eventual divinization or sanctification of the self unto God (theosis). This classical paradigm has influenced just about every Christian intellectual, be it western or eastern. The Lublin School agrees with this format but differs in terms of methodology. While Garrigou-Lagrange read Aquinas as "hard" as he possibly could, Lublin Thomism seeks to use the philosophies of phenomenology and existentialism to better understand the human experience in terms of faith. Notable thinkers here are Mieczys?aw Albert Kr?piec, who is considered the founding figure of the Lublin School, and Karol Wojty?a, known to the world as John Paul II; This school of thought was found as a reaction to the rise of the Polish Communist Party and was seen as an attempt to combat Marxism. The major difference between a Garrigou-Lagrange and the Lublin Thomist's is the emphasis on personalism, a modern philosophy that asserts that the human person is a free responsible moral agent made in the image of God; Garrigou-Lagrange was almost always critical of modern philosophies. I think we should take Garrigou-Lagrange to heart; The outline of his mysticism is wonderful and very practical. However, the personalistic stance of Lublin Thomism is much more applicable to questions about everyday life.

The Impact of Kierkegaardian Existential Theology

Soren Kierkegaard is known to history as a melancholy Dane but a bright intellectual; John Paul II was known to have been an admirer of Kierkegaard, as his thought meshes well with Lublin Thomism. To breakdown his thought, man lives in a state of despair which is sin. When confronted with two moral extremes we experience anxiety, which according to him is our ability to feel total freedom. The aesthetic life is a life guided by pleasure; We rarely take into the account the consequences of our actions. The ethical life is a life guided by rational inquiry into what we do and say. This ultimately is followed by the religious life, taking a "leap of faith" into the hands of the Unknowable God. Jesus Christ is considered by Kierkegaard the ultimate paradox because of the idea that Christ is the God-Man, the connection between the physical and the spiritual. Kierkegaard meshes well with the Lublin School because of their focus on human experience while not falling into relativism. Kierkegaard constantly spoke of Christendom being without Christians because he felt many of the established churches fell short from "New Testament Christianity."

Holy Orthodoxy as an expression of New Testament Christianity

This leads me to discuss the spirituality and praxis of the Eastern Church. Orthodoxy is an ancient tradition that is older than the Tridentine Mass and Protestant services based upon that. The Divine Liturgies of the various Orthodox Churches as well as Eastern Catholic Churches have a much older feel. Culturally these churches do not like change at all. The practice of hesychasm, contemplative prayer using the Jesus Prayer ("Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner"), is the heart of Orthodox praxis. This practice grounded in the intellectual tradition of Palamism, the thought of St. Gregory Palamas, is a gateway into a mysticism that is not only practical but an expression of New Testament Christianity. Roman Catholics and Protestants don't need to do away with their traditions in order to integrate this into their spiritual life; The format of hesychasm follows the patristic model of mysticism that Fr. Garrigou-Lagrange attempts to model. In conclusion, the legacies of these great intellectual and theological traditions provide a route to unravel what New Testament Christianity really is all about.

Comments (38)

Quoting Dermot Griffin

When one does away with tradition, it makes them much more prone to falling into a state of religious relativism, which affects what they believe about essential doctrines. John Wesley saw the need for a more personal relationship between God and humans and thus started a movement that was founded upon the ideals of faith through practice (which gets to your points made about Orthodoxy). The problem that Methodism saw is that people were susceptible to falling from tradition because of the priority placed on religious experience and their neglect of scripture and tradition. It is sad to see that many people today call themselves Christians and yet are not even followers of Christ. I admire my Catholic and Orthodox brothers and sisters and, at times, envy them due to their unshakeable faith and rigorous practices.

Albert Outler coined a term known as the "Wesleyan Quadrilateral" that explains the importance of a synthesis between experience, reason, scripture, and tradition. I particularly like this system because it is similar to the checks and balances system that we see in the United States government. That way, not one aspect of the Christian faith can distort a Christian's perspective.

I appreciate your reply. I am probably going to make a post on the use of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism as apologetical tools to argue for Christianity. I often think that fellow Christians see them as just different philosophical traditions or religions (especially Buddhism) and do not realize the worth they have as lens to view the Bible from.

[quote=Brief Overview of Lublin Thomism;https://www.angelicum.net/classical-homeschooling-magazine/fourth-issue/brief-overview-of-lublin-thomism/] Saint Thomas presents a philosophy based on existence, which we may call existentialism (but we must avoid any confusion with the philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre in this regard).[/quote]

That aspect of 'existentialism' appeals to me because of the understanding that 'being is an act'. About the only reading I've done in the area are some brief readings of Jacques Maritain but I believe he is also part of the same broad school of thought. I have been impressed by his essay, The Cultural Impact of Empiricism, because I have become convinced of the reality of universals and aspects of scholastic realism. I also realise that I have been very much influenced by Christian Platonism - I think it's a kind of inborn cultural archetype. Consequently some of the Catholic philosophers I've encountered are intuitively appealing, although I don't feel much drawn to the Church.

Quoting Dermot Griffin

I've been a student of Buddhism a lot of my adult life, even completing an MA in the subject, and participating in a discussion group for many years. I kept up the practice of sitting meditation as per Buddhist principles for many years, but fell out of the routine three years ago, and haven't gone back to it. I've become sceptical of Western Buddhism - that is, Buddhism as practiced and propogated in modern culture. And while I have considerable respect for the teaching and principles I don't feel as though I've been able to successfully integrate into them or with them. I did have some real epiphanies associated with meditation earlier in life, but then it's been like a 'seeds and weeds' scenario in the subsequent years. (I'm in a quandary about it, although I suppose internet forums aren't really a good medium to air such things.)

This is very interesting and I have to say I feel for you. Has this change in focus been responsible for drawing you to some of the richer, earlier traditions of Christianity? I get that this is a hard topic, so feel free to move on. I think it would be interesting to understand more about your position on Buddhism - do you think this reflects personal factors, or is it perhaps something intrinsic to Westerners? I wonder if cultural fit is important in spiritual journeys - obviously the notion a higher awareness transcends culture, but the path along the way seems to be bound to it.

What do you mean by "mystical theology?" I find this to be a tricky term. Is mysticism just "experience of God?" Something like "knowing God the way a biographer/historian knows a person" (theology) versus "how their spouse knows that person," (personal/mystical)? This was Jean Gerson's expansive view in the 14th century, one used by some modern scholars, e.g. Harmless.

Or is mysticism about ecstasies, peak experiences, and visions, as William James would have it?

Or is this the "mystical theology," of Pseudo Dionysus (Saint Denis), an apophatic revelation of the "Divine Nothingness?"

It seems to me like the mystical tradition is generally much weaker in Protestantism. When it does manifest, it is much more often as more concrete, supernatural experiences: exorcisms, healing, visions, etc. I tend to be skeptical of these, both because of the historical ways they have been revealed to be hoaxes and because of my personal experiences with people who seem to be more living out a sort of self-serving fantasy life for themselves in this way, although I'm sure this isn't always the case.

However, the Catholic tradition still seems to have a fairly robust concept of mysticism. You have guys like Thomas Merton, James Finley, and of course the active orders of contemplative monks and nuns who still attract new novices.

It isn't always strong in individual churches, but it seems to be a decently strong undercurrent in the tradition. The communal praying of the Rosary is itself the sort of thing that is common in mystically oriented traditions, and I see the even at my local church. Although, only in the cathedrals of Latin America (Quito in particular) and Rome have I seen people in apparent ecstasies before the altars.

The Orthodox tradition I am less personally familiar with. It does seem to have a large focus on mysticism, perhaps more than the Catholic tradition, which has made room for a great deal of rationalism (Saint Thomas's "two winged bird" and all. But then again, the Orthodox Churches also seem to get more tied up in nationalism and performative tradition, particularly in Russia.

The Philokalia does have more stuff focused on mysticism than a Catholic reader might, but the Catholic tradition will still have Augustine's beatific vision, Pseudo Dionysus (a well spring for both, along with Gregory of Nysa), Saint Bonaventure and the vision of Saint Francis and the Seraphim, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, or Hildegard.

Apparently, in terms of tradition, the Oriental Churches and the Eastern Catholic Churches, e.g. the Chaldean Church, have the closest liturgy and worship setting to the early church. A good deal dates to the 4th century. I find it interesting how some of these had an easier time rejoining the Roman Catholic church than the more similar Eastern Orthodox churches in light of that. But they've kept their traditions despite the merger.

As Saint Athanasius famously put it (quoting Saint Irenenius): "God became man that man might become God."

This isn't an elevation of man, but rather a transformation and union. Saint Paul stalks about "putting on the new man." Christ talks about being "reborn." The result is Christ as a bridge to the Divine Nature, through the Spirit. Saint Paul, Saint John, and Saint Peter all talk about "God living in us," "living in God," "Christ living in us," "I must decrease and Christ must increase," etc. We hear of living in the "fullness (pleroma) of God."

I also tend to agree with Tilich that competition with Islam (and later the Reformation) wounded the universality of Christianity. It became "one religion among many," as opposed to a universal, non-religion. The Patristics' sense of Christ as Logos had it that all knowledge was ultimately grounded in the divine. It was so easy for them to assimilate Platonism and Aristotle. The Logos was present in all cultures and religions, and all men craved the "true good," the "real truth." This sort of universalist self-confidence has been badly damaged though. You still see it in later figures though, Erasmus, Cusa, Boheme, Zwingli, Hegel, etc.

Thomism is probably a place where that sort of sentiment survives.

Same here.

I get the sense that Buddhism is parasitic on Hinduism, and that trying to attach oneself to Buddhism without the benefit of Hindu culture is something of a non-starter. Similarly, I find interreligious dialogue between Catholicism and Hinduism to be more apropos and compelling than interreligious dialogue between Catholicism and Buddhism. Much like Protestantism, there is something incomplete about Buddhism. It is a religion working from a borrowed culture, and one which is founded on a critique of the more comprehensive religion which is properly attached to that borrowed culture. In both the Buddhist and Protestant cases there is the implicit claim that the cultural divorce is a feature and not a bug, and that's a rather difficult subject to query, but in the end I'm not so sure. I think religion and culture must ultimately go together, and that all attempts to indefinitely separate them are unrealistic.

What follows is that Buddhism and Protestantism do not transplant well. They do not possess the wherewithal to endure a foreign environment without becoming subsumed by it. Or if they do manage to survive, they do not possess the resources to produce and sustain a robust culture of their own. Thus such movements are short-lived on foreign soil.

...Also, in general I am wary of religions started by a single individual (e.g. Buddhism, Islam, Protestantism). Jesus is the exception if we accept the premise that he is divine, although we could also argue over whether he was, strictly speaking, a founder. There is something more organic, comprehensive, and compelling about religions like Hinduism, or Judaism, or even Taoism. But also more messy and unwieldy.

Quoting Wayfarer

There seem to be a growing number of agnostic intellectuals who favor Christian culture and a Christian worldview, but who remain a step removed from Christian belief. Roger Scruton, Douglas Murray, and Tom Holland come immediately to mind. Part of this seems to be a backlash against the dull iconoclasm of the New Atheism, part of it a response to Marxist ideologies, but a lot of it seems to be a legitimate appreciation of the Christian patrimony and inheritance. This is all rather interesting to me, because Joseph Ratzinger often argued precisely in favor of such a move ("veluti si Deus daretur"). I always found the argument awkward, but apparently it has some purchase. Supposing religion and culture are inextricably linked, it makes sense that some would defend a religion for the sake of a culture.

Quoting Wayfarer

This strikes me as a ubiquitous and perennial difficulty, namely that we are bound by our geography. The ideal of a strong 'guru' figure must often be foregone on account of this.

Quoting Count Timothy von Icarus

Yes, but I think Islam and Protestantism were just precursors to the inevitable pluralistic religious setting we now find ourselves in in the West. Presumably there is a natural ebb and flow between polytheism and monotheism over the millenia, and now the information age has shifted us back towards a more polytheistic orientation. What was once a cultural-religious whole has now become increasingly fractured.

Jacob Böhme being an exception, although subject to severe criticism from the pulpit, but a big influence on German romantics.

Quoting Count Timothy von Icarus

:100: There was no sense of that dimension in the Christian teachings I received in childhood. It was very much learn by rote and follow the rules. That leads to the dessicated social religion that Christianity has become - 'belief without evidence' as it's usually described here. And that is because so much of the symbolism is derived from the 'spiritual ascent' and only makes sense in relation to that. Now that I understand that, I'm re-considering!

(I've often remarked that the whole purpose of today's culture is to accomodate the human condition, to make it as comfortable as possible, whereas the aim of spiritual culture is to transcend it. It's a hard truth.)

That second image in the OP is associated with The Ladder of Divine Ascent. The article contains a translation, which I shall read.

Quoting Leontiskos

Oh, I don't know about that. I mentioned Zen Catholicism, and I've seen some estimable teachers from that school. There are many points of convergence. I also saw the Venerable Bede Griffith, not long before his death - very frail but still vital and serene - a Catholic monk who had settled in an Indian ashram.

Venerable Father Bede Griffith

Quoting Leontiskos

Buddhism has been a very successful cultural export. From its origins in Maghada in Northern India, it spread along the Silk Road to become a major world religion, indeed the principle religion of Eastern culture.

I've absorbed some crucial elements from Buddhism - not beliefs so much as cognitive skills - which will always stay with me. Whatever doubts I harbor are not about it, but about me.

I think the "dessicated social religion" part is very true, provided you're talking about mainstream U.S. Christian denominations -- perhaps not the best sample.

"Belief without evidence" is trickier. There's all kinds of evidence for the existence of God and even the divinity of Jesus, but none of it is rock solid. As in so many areas, we're left with beliefs that fall far short of certainty, but are hardly as bereft as "belief without evidence" sounds. In my opinion (and experience), a direct encounter with the mystical is extremely powerful evidence in support of theism. It isn't self-validating, but the "God hypothesis" can be compared critically with other explanations for the experience, and I can decide that the other explanations aren't as plausible -- as indeed I have.

Have you ever tried LSD, as a basis for comparison of altered states that you can experience?

I can certainly understand mystical states of mind as having an intensity that can be surprising, and how people can easily be inclined to think a non-mundane explanation is needed. However, "powerful evidence"?

Have I ever! Don't get me started . . . :starstruck:

I don't mean to make this just about me, but the (non-LSD) experience I had, some 35 years ago now, has stubbornly resisted being reduced to psychological categories. I certainly tried, as did most of my concerned friends. The main reason I call it strong evidence is that it changed my life in a way that was immediate, profound, and long-lasting, and made sense of all the previously senseless God-talk I'd heard. I think William James has the best descriptions of this sort of thing in Varieties of Religious Experience, but there are many Eastern accounts as well.

Could I be wrong? Sure -- no certainty, as I said. But I'm satisfied to have found the most likely explanation.

FWIW, the fact that you have such a basis for comparison makes me more interested in hearing more.

Totally with you on all that. But the accusation of belief without evidence is often raised on this forum whenever any vaguely religious sentiment is expressed. In the context of today's culture, science is implicitly understood as the arbiter of what should be taken seriously, so to argue for anything deemed metaphysical or mystical is generally relegated to the domain of faith - it may be edifying, but you have no way of showing that it's true. Part of this is that, not only Biblical texts, but the literature of all the traditions of the sacred, are presumed to lack any evidentiary value, because, for instance, 'all the religions make competing claims to the one truth, how could any of them be right?' (I get that a lot.)

Quoting wonderer1

Back in the day. I'm a sixties person and it was around then, in fact when I first tripped, it hadn't been banned yet. It can be (although not always is) like a window to another dimension of existence. The memories I retain are a sense of rapture at the extraordinary beauty of natural things, some vivid hallucinatory experiences, and a sense of 'why isn't life always like this?'

I dont know if youve read Walker Percy. He makes an interesting distinction between knowledge and news. Knowledge would be the sort of thing that, broadly, science investigates. News, on the other hand, is information that you cant deduce or discover for yourself; someone has to tell you. This would include religious revelation, for Percy. And he says that the credentials of the news-bearer are important evidence for whether to trust the news.

This may be too black-and-white, but I see what hes getting at and I think its a valuable insight. I wonder what Aquinas would say, getting back to the OP. He made a distinction between natural and revealed religion, didnt he? And I'm sure Kierkegaard, that champion of subjectivity, would agree.

Consider this passage from Buddhist scholar, Edward Conze:

This maps quite well against the table that is provided in the OP.

My belief is that there is a real qualitative dimension, the vertical axis - which I think is the minimum possible requirement for a spiritual philosophy. But this is non-PC in secular culture, which is a flatland as far as values are concerned: every individual is his or her own arbiter of value, and any claims to 'higher knowledge' amount to authoritarianism and dogma.

For me it was the early 80s. I didn't have vivid hallucinations, although people I tripped with did. (I suspect I may be towards the aphantasic end of a aphantasia-hyperphantasia spectrum.)

But yes, the overwhelming beauty of everything was wonderful to experience.

Not only that, but the meaning of "evidence" to some here has been so narrowed down by empirical principles, that it could only mean something which appears directly through an individual's sensations. This effectively renders "evidence" as completely subjective which is the exact opposite to what these people intend.

This is the result of removing the requirement of a logical relation between the thing which is evidence, and the thing which it is evidence of. And this logical relation is the essence of "evidence". The empiricist attempt to remove this necessary logical relation, to make "evidence" an empirically based concept would render the concept completely subjective and worthless.

And validated in peer-reviewed science journals!

I've often reflected, when Dawkins waves his hands around and says 'but where is the evidence??' that any believer could simply say 'you're standing in it!'

"Accepting science as a way of understanding the natural world entails rejecting claims about this world that are incompatible with science, such as claims about witches and spirits. But accepting a scientific view of the natural world does not mean accepting the view that the only meaningful statements with determinate truth values are statements about the natural world." (from Being Realistic About Reasons, 2011)

Also this, from Thomas Nagel:

"It is not one of the claims of natural science that natural science contains all the truths there are." (from Analytic Philosophy and Human Life, 2023)

These philosophers are drawing attention to one of the most common misunderstandings of what science does. There is no "completeness theorem" for truths either entailed or revealed by science -- only scientism would try to make such a claim.

I really enjoy Walker Percy, but it's been a few years since I've read him. Recently I have been reading Pascal, Kierkegaard, and Johann Georg Hamann: three nice counterbalances to the rationalism of this forum. Here is a characteristically polemical utterance from Hamann, haha:

(The context here is a metacritical response to Moses Mendelssohns Jerusalem.)

Quoting J

Aquinas is more or less in agreement with Percy. Here is the body of an article on whether theology (sacred doctrine) is a matter of argument:

Quoting Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, Ia, Q. 1, A. 8

For Aquinas an article of faith cannot be demonstrated or refuted by natural, philosophical reasoning. Thus someone who denies an article of faith cannot be argued into the position, even though their positive objections can be met. The difference between Aquinas and Percy would seem to be that, for Aquinas, revelation ("news") is not restricted to things that are in-principle indemonstrable. For example, Aquinas believes that "the universe had a beginning" is a revealed truth. Aristotle argues from natural reason that the universe had no beginning, and so Aquinas sets himself to meeting and nullifying Aristotle's arguments.

Aquinas also makes a distinction between natural and revealed religion, but his distinction between natural and revealed knowledge seems more appropriate. I tend to agree with him that, in the broad sense, 'religion' is not primarily a matter of knowledge.

I don't know if it's true of those traditions, but what has been handed down. The sapiential and practical sides of the disciplines have been ignored or treated as secondary, whereas in reality, that is the way that the ideas 'come to life'. Have a read of Karen Armstrong's metaphysical mistake.

Well, I think what is going on is slightly different. For Aquinas faith is always related to a proposition. My understanding is that when he speaks about "objections against faith," 'faith' is something like a superset of the articles of faith. An article of faith would be akin to an axiom in the sphere of revelation, whereas 'faith' would include not only the axioms but also the conclusions inferred from the axioms. This is a simplification, as Aquinas' treatment of faith is rather subtle, but it seems generally true. Some Protestants are known for speaking about faith in an entirely non-propositional sense, but for Aquinas this would be a kind of hope (i.e. hoping and trusting in God or his promises).

So in that quote, with respect to faith, Aquinas is saying that faith-propositions can only be known by revelation and not by natural reason. For someone who holds at least one faith-proposition, that proposition can be leveraged in order to infer and argue about other faith-propositions. For someone who holds no faith-propositions, there is no possibility of demonstrating (strict scientia) the truth of a faith-proposition. All the same, if someone says, "X faith-proposition is false, and here is a proof for why," Aquinas thinks the proof can be addressed and refuted, even though no contrary proof for the faith-proposition is possible. Or in simpler terms, when it comes to unbelievers Aquinas thinks it's all defense and no offense (although this is complicated because certain things we take to be faith-based Aquinas thinks are accessible to reason, such as the existence of God).

Quoting J

Aquinas certainly thinks it generalizes to other sciences, and I think he would also affirm this of other worldviews. Granted, as you say, metaphysics is in a rather unique situation, as it seems to be able to establish itself in certain ways (and this goes back to our conversation about whether one could actually deny something like the law of non-contradiction).

Quoting J

I think this is right, but I should add that for Aquinas one of the easiest ways to show that scientific knowledge is possible is simply to show a scientific truth. If we know a scientific truth then obviously scientific knowledge is possible.

I think the relevant difference is that scientism holds to scientific truths, and these really are demonstrable from natural reason, whereas faith-propositions (and fundamentally the axioms, the articles of faith) are not. The error of scientism lies in holding that the truths of the hard sciences are the only truths.

On a deeper level, surely the 'corruption of the intellect' due to man's fallen nature is a factor? There's an interesting scholar, Peter Harrison, who's book The Fall of Man and the Foundations of Science, 'shows how the approaches to the study of nature that emerged in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were directly informed by theological discussions about the Fall of Man and the extent to which the mind and the senses had been damaged by that primeval event. Scientific methods, he suggests, were originally devised as techniques for ameliorating the cognitive damage wrought by human sin.'

'Scientism' would recognise no such thing, as it's plainly a theological rather than scientific conception. But it's also the sense in which 'revealed truth' has epistemic as well as simply moral implications. 'Fallen man' does not 'see truly' so to speak, because of that corruption. (In Eastern religions, the term is 'avidya' rather than 'sin' and has a rather different connotation, in that it's associated with the corruption of the intellect rather than the will, which is especially the case in Reformed theology. But there are overlaps.)

I am not familiar with that thesis, so I can't really comment one way or another, but it sounds interesting. Looking at the table of contents, the trajectory he traces seems like a plausible support for the argument.

Quoting Wayfarer

Which is to say that Scientism is a great deal more optimistic about the possibility and accessibility of scientific knowledge? I could definitely see that. I think now, post-Covid, some pessimism is setting in again, and this also flows from things like John Ioannidis' Why Most Published Research Findings are False.

Quoting Wayfarer

Right, and I would agree that the intellect is fallen. Also, I would say that the interdependence of moral and speculative knowledge is still operative in our fallen world. But you are right that there has been a strong separation.

Hey don't get me wrong, I'm very bullish about science and technology. But there's a missing dimension, without which it might easily loose its moral compass. Look at the turmoil that's engulfed OpenAI - don't know if you've been following, but the charismatic young CEO, Sam Altmann, was suddenly sacked by the Board last Friday, then there was a staff revolt, they all threatened to follow him out the door and join Microsoft, and he was re-hired as of yesterday. The issue? Allegations that he was putting profits ahead of ethics in product development. And it's a legit concern! On the other hand, though, I'm a big fan of ChatGPT, I've been using if, mainly for philosophy research, since Day 1, and it's incredible. The depth of conversation and nuances are really remarkable.

But then, also bear in mind that Aquinas saw no conflict between Science and Faith, unlike the Protestants. This is where I'm suspicious of the motives of Luther and Calvin. There has to be a world where both faith and science can co-exist, instead of the former feeling constantly threatened by the latter. But likewise, it is essential that the objective sciences recognise the limitations of objectivity. We're all participants in existence.

Ahah, I see. Thanks for the clarification. Argumentation is possible within the "world" made possible by articles of faith, but the articles themselves, and that world, can't be demonstrated, only defended from (necessarily false) refutations. Is this closer?

- Thank you! I downloaded a copy.