The Meta-management Theory of Consciousness

The Meta-management Theory of Consciousness uses the computational metaphor of cognition to provide an explanation for access consciousness, and by doing so explains some aspects of the phenomenology of consciousness. For example, it provides explanations for:

1) intentionality of consciousness - why consciousness "looks through" to first-order perceptions etc.

2) causality - that consciousness is "post-causal" - having no causal power over the event to which we are conscious, but having direct causal effect on subsequent events.

3) limited access - why we only have conscious experience associated with certain aspects of brain processing.

https://malcolmlett.medium.com/the-meta-management-theory-of-consciousness-17b1efdf4755

I know that I am going to get roasted by this wonderful and thorough community, but I wanted to share my theory both for your own enjoyment and so that I can learn from the discussions. Some of you might remember me from a long time ago. Those discussions were extremely useful, and have helped me entirely revise both my theory and how I describe it. I really hope that you'll enjoy this. Roast away.

I'll try to summarise here as best I can. The details are in the blog post - it's only a 40 minute read.

I'll explain it here in two parts. The first part is the computational argument, which depends on knowledge of predictive processing paradigms such as that of Predictive Coding or the Free-Energy Principle. I know that it's easy to get lost in the details, so I'll try to summarise here just the key takeaways.

The second part will focus on how I think my theory makes headway into the trickier philosophical debates. But bare in mind that I'm a little clumsy when it comes to the exact philosophical terminology.

Computational background:

Causality. One of my favorite learnings from this exercise is that consciousness is what I call post-causal. Events unfold as follows: 1) the brain does something, 2) the MMFL captures that something and makes a summary of it available as a cognitive sense, 3) the brain gets to consider the cognitive sense that is now being received. Anything that the brain considers "now" in relation to the cognitive sense is about something happened earlier. Thus our conscious experience of cognitive activity is always one step behind. Consciousness has no causal power over its intentional object. However, conscious access very much has causal power over everything that follows.

Phenomenological Consciousness. I doubt that I have the philosophical savvy to make any real headway in arguing that MMT explains the existence of phenomenological consciousness. But I do believe that it does and I'll try to state the beginnings of an argument.

1) intentionality of consciousness - why consciousness "looks through" to first-order perceptions etc.

2) causality - that consciousness is "post-causal" - having no causal power over the event to which we are conscious, but having direct causal effect on subsequent events.

3) limited access - why we only have conscious experience associated with certain aspects of brain processing.

https://malcolmlett.medium.com/the-meta-management-theory-of-consciousness-17b1efdf4755

I know that I am going to get roasted by this wonderful and thorough community, but I wanted to share my theory both for your own enjoyment and so that I can learn from the discussions. Some of you might remember me from a long time ago. Those discussions were extremely useful, and have helped me entirely revise both my theory and how I describe it. I really hope that you'll enjoy this. Roast away.

I'll try to summarise here as best I can. The details are in the blog post - it's only a 40 minute read.

I'll explain it here in two parts. The first part is the computational argument, which depends on knowledge of predictive processing paradigms such as that of Predictive Coding or the Free-Energy Principle. I know that it's easy to get lost in the details, so I'll try to summarise here just the key takeaways.

The second part will focus on how I think my theory makes headway into the trickier philosophical debates. But bare in mind that I'm a little clumsy when it comes to the exact philosophical terminology.

Computational background:

- The theory starts with a computational discussion of a particular problem associated with cognition: namely deliberation. Here I am using cognition to refer generally to any kind of brain function, and deliberation to refer to the brain performing multiple cycles of processing over an arbitrary period of time before choosing to react to whatever stimuli triggered the deliberation. That is in contrast to reaction where the brain immediately produces a body response to the stimuli.

- I argue for why deliberation is evolutionarily necessary, and why it is associated with a considerable step up in architectural complexity. Specifically that it is "ungrounded" from environmental feedback and can become unstable. To resolve that it requires meta-cognitive processes to "keep it in check". I label the specific meta-cognitive process in question as meta-management.

- Meta-management is best described in contrast to 1st-order control. Under 1st-order control, a 1st-order process has the task of controlling the body to respond appropriately to the environment and to homeostatic needs. A meta-management process is a 2nd-order process tasked with the control of the 1st-order process, particularly from the point of view of the homeostatic needs of that 1st-order process. For example, the 1st-order deliberative process can become ungrounded as mentioned before, and it is the task of the 2rd-order process to monitor and correct for that. In the blog post I explain my concretely what I mean by all this.

- I propose a functional structure whereby the 1st-order order process can meta-manage itself without the need for an explicit separate 2nd-order system. I explain how this is possible via predictive processes (think bayesian inference), in conjunction with a special kind of feedback loop - the meta-management feedback loop.

- The Meta-management Feedback Loop captures certain aspects of the current state of cognitive processing and makes them available as a cognitive sense, which is perceived, processed, modelled, predicted and responded to like any other exteroceptive or interoceptive sense. I provide a computational and evolutionary argument for why such a feedback loop captures only a minimal amount of information about cognitive processes.

- While it seems at first counter-intuitive that such a system could work, I argue how it is possible that a 1st-order process can use this feedback loop for effective meta-management of itself.

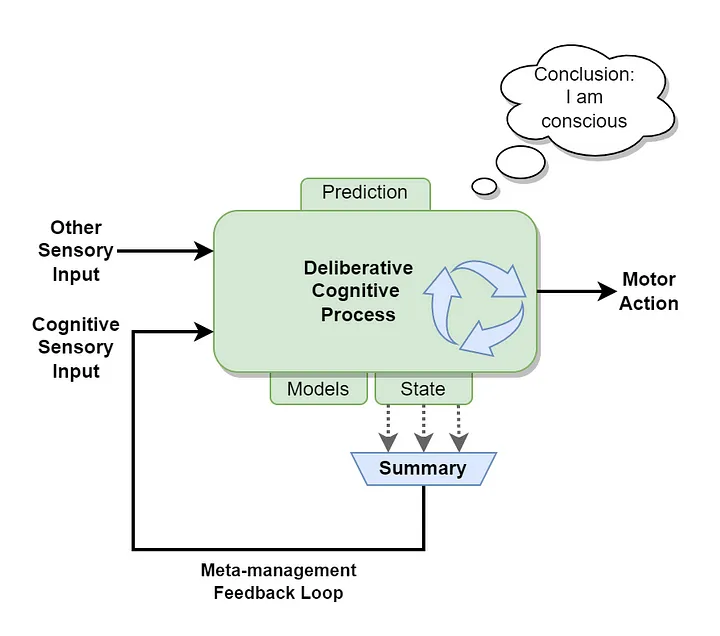

- Looking at just cognition alone, this provides a general framework for understanding deliberation, and by extension for human's ability for abstract thought (I explain this last point briefly in the blog post, and in more detail in another if anyone is interested to know more).So that all leads to this functional structure which I argue is a plausible mechanism for how human brains perform deliberation and how they keep their deliberative processes "grounded" while doing so:

I have no strong empirical evidence that this is the case for humans, nor even that my suggested architecture can actually do what I claim. So it's a thought experiment at the moment. I plan to do simulation experiments this year to build up some empirical evidence.Implications for understanding Consciousness:Now I shall try to argue that the above explains various aspects of access consciousness, the phenomenology of consciousness (ie: specific identified characteristics), and that it might even explain the existence of phenomenological consciousness itself.Conscious Contents. The Meta-management Theory of Consciousness (MMT from hereon) suggests that the contents of consciousness is the result of whatever is fed back as a sensory input via the Meta-management feedback loop (MMFL). The predictive theory of perception suggests that cognitive processes in relation to exteroceptive and interoceptive sensory signals do not take those signals literally and use them in their raw form throughout. Rather, the brain first uses those sensory signals to predict the structure of the world that caused those sensory signals. This creates a "mental model" if you will, of what is "out there". The cognitive processes then operate against that model. I propose that the same goes for the sensory signal received via the MMFL. This creates a cognitive sense that is processed in the same predictive fashion as for other senses. To be clear, I mean that the "cognitive sense" provides a sensory signal about the immediately prior cognitive activity, in the same way that a "visual sense" provides a sensory signal about optical activity. And that then this cognitive sense is subject to the same predictive processes that create a "mental model" of the structure of whatever caused that cognitive sensory signal.Here I am talking about access consciousness. Why do we have access consciousness at all? I propose that it is because of the MMFL and its associated cognitive sense. There's nothing new in my proposal that we have access consciousness because the brain has access to observe some of its own processes. What's novel is that I have grounded that idea in a concrete explanation of why it might have evolved, in the specific computational needs that it meets, and in the specific computational mechanisms that lead to that outcome.Intentionality. MMT provides the background for Higher-Order Thought (HOT) theory. It describes that the cognitive sense is a HOT-sense - a specific second-order representation of the first-order process. I won't go on at length about this but I'll draw out some specific nuances (again, there's more details in the blog post):[list]

I have no strong empirical evidence that this is the case for humans, nor even that my suggested architecture can actually do what I claim. So it's a thought experiment at the moment. I plan to do simulation experiments this year to build up some empirical evidence.Implications for understanding Consciousness:Now I shall try to argue that the above explains various aspects of access consciousness, the phenomenology of consciousness (ie: specific identified characteristics), and that it might even explain the existence of phenomenological consciousness itself.Conscious Contents. The Meta-management Theory of Consciousness (MMT from hereon) suggests that the contents of consciousness is the result of whatever is fed back as a sensory input via the Meta-management feedback loop (MMFL). The predictive theory of perception suggests that cognitive processes in relation to exteroceptive and interoceptive sensory signals do not take those signals literally and use them in their raw form throughout. Rather, the brain first uses those sensory signals to predict the structure of the world that caused those sensory signals. This creates a "mental model" if you will, of what is "out there". The cognitive processes then operate against that model. I propose that the same goes for the sensory signal received via the MMFL. This creates a cognitive sense that is processed in the same predictive fashion as for other senses. To be clear, I mean that the "cognitive sense" provides a sensory signal about the immediately prior cognitive activity, in the same way that a "visual sense" provides a sensory signal about optical activity. And that then this cognitive sense is subject to the same predictive processes that create a "mental model" of the structure of whatever caused that cognitive sensory signal.Here I am talking about access consciousness. Why do we have access consciousness at all? I propose that it is because of the MMFL and its associated cognitive sense. There's nothing new in my proposal that we have access consciousness because the brain has access to observe some of its own processes. What's novel is that I have grounded that idea in a concrete explanation of why it might have evolved, in the specific computational needs that it meets, and in the specific computational mechanisms that lead to that outcome.Intentionality. MMT provides the background for Higher-Order Thought (HOT) theory. It describes that the cognitive sense is a HOT-sense - a specific second-order representation of the first-order process. I won't go on at length about this but I'll draw out some specific nuances (again, there's more details in the blog post):[list] - The intentionality of access consciousness is the behavior of the first-order cognitive processing system. It exists to support meta-management, which needs to monitor that behavior. This means that the intentionality is not of our first-order perceptions, per se, nor even of our thought, per se. Rather, it is the static and dynamic state of the first-order process while it operates against those first-order perceptions/thoughts/etc. In a very practical way, that static and dynamic state will inevitable capture aspects of first-order perceptions and thoughts, but it will always be by proxy. The cognitive sense about the immediately prior cognitive activity represents the fact that the brain was thinking about an apple that it sees, rather than directly representing the apple seen. Or perhaps the cognitive sense represents that the brain was at that moment attending to the visual perception of the apple, and thus by proxy the cognitive sense captures many aspects of that visual perception, but not the actual visual perception itself.

- In contrast to some debates about HOTs versus HOPs (higher-order perceptions), MMT suggests that the cognitive sense is a higher-order representation of cognitive activity in general. Thus it is neither accurate to refer to it as a higher-order thought nor as a higher-order perception. Better terms could be Higher-order State or Higher-order Behavior.

Causality. One of my favorite learnings from this exercise is that consciousness is what I call post-causal. Events unfold as follows: 1) the brain does something, 2) the MMFL captures that something and makes a summary of it available as a cognitive sense, 3) the brain gets to consider the cognitive sense that is now being received. Anything that the brain considers "now" in relation to the cognitive sense is about something happened earlier. Thus our conscious experience of cognitive activity is always one step behind. Consciousness has no causal power over its intentional object. However, conscious access very much has causal power over everything that follows.

Phenomenological Consciousness. I doubt that I have the philosophical savvy to make any real headway in arguing that MMT explains the existence of phenomenological consciousness. But I do believe that it does and I'll try to state the beginnings of an argument.

- 1) All exteroceptive and interoceptive senses undergo transformation from raw signal to a prediction of the world structure that caused them. In some circles this is known as the inferred latent state. I believe that the brain doesn't just infer the latent state, but also associates other meaning such as an inference of how that particular latent state relates to the needs of the individual. So, for example, the perception of a lion without any protection in between is associated with knowledge of danger. Part of that associated meaning is identification of self vs other (I know that the lion is other, and that my body is part of my self, and that it is my body that is in danger). This depends on a mental model of what a "self" is.

- 2) In the same way, our cognitive sense can be further processed and meaning associated to it. In particular, identification of the relationship between the cognitive sense and the "self". Thus any further cognitive processing of this cognitive sense has immediate access to the full enriched concept of "self" and its relationship to to whatever the cognitive processes were doing immediately beforehand. This would seem to me to be the underlying mechanism behind what Nagal called "what it feels like" to be conscious.

Comments (59)

https://aeon.co/essays/how-blindsight-answers-the-hard-problem-of-consciousness

I have to credit @Luke for pointing it out to me.

Your diagram interesting looks very similar to one I created myself many years ago. I did approach it from a different angle but it has all the same major components with the exception of a "Time front".

I tried to tackle the idea that in an illustration of the "conscious sphere of awareness" where is the "present", "past" and "future" to which we remember, currently feel and likewise anticipate or as you say "predict" when realistically, all active conscious thought occurs only in the present.

My diagram was something of a tear drop shape but on it's side. Like a hot air balloon but horizontal. With memorised information lagging behind in chronological timeline and dissipating (being forgotten) - accessed of course only from the present moment (near the base of the teardrop).

Forgive me if I'm not explaining it well.

Thanks. Something I've suspected for a while is that we live in a time when there is enough knowledge about the brain floating around that solutions to the problems of understanding conscious are likely to appear from multiple sources simultaneously. In the same way that historically we've had a few people invent the same ideas in parallel without knowing about each other. I think Leibniz' and Newton's version of calculus is an example of what I'm getting at. So I'm not surprised to see Nicholas Humphrey saying something very similar to my own theory (for context, I've been working on my theory for about 10 years, so it's not that I've ripped off Humphrey). Humphrey also mentions an article by Anil Seth from 2010, which illustrates some very similar and closely related ideas.

MMT depends on pretty much all the same mechanisms as both Humphrey's and Seth's articles. Modelling. Predictive processing. Feedback loops. The development of a representational model related to the self and cognitive function - for the purpose of supporting homeostatic processes or deliberation. Seth's article pins the functional purpose of consciousness to homeostasis. He explains the primary mechanism via self modelling, much like in my theory. Humphrey pins

Humphrey proposes an evolutionary sequence for brains to go from simple "blindsight" stimulus-response to modelling of self. That's also very much consistent with MMT. He pins the purpose of consciousness on the social argument - that we can't understand others without understanding ourselves, and thus we need the self-monitoring feedback loop. Sure. That's probably an important feature of consciousness, though I'm not convinced that it would have been the key evolutionary trigger. He proposes that the primary mechanism of consciousness is a dynamical system with a particular attractor state. Well, that's nice. It's hard to argue with such a generic statement, but it's not particularly useful to us.

So, what benefit if any does MMT add over those?

Firstly I should say that this is not a question of mutual exclusion. Each of these theories tells part of the story, to the extent that any of them happen to be true. So I would happily consider MMT as a peer in that mix.

Secondly, I also offer an evolutionary narrative for conscious function. My particular evolutionary narrative has the benefit that is is simultaneously simpler and more concrete than the others. To the point that it can be directly applied in experiments simulating different kinds of processes (I have written about that in another blog post) and I plan to do some of those experiments this year. At the end of the day I suspect there are several different evolutionary narratives that all play out together and interact, but egotistically my guess is that the narrative I've given is the most primal.

Thirdly, my theory of how self-models play out in the construction of conscious contents is very similar to that of Seth's article. Incidentally, Attention Schema Theory, also proposes such models for similar purposes. I think the key benefit of MMT is again its concreteness compared to those others. I propose a very specific mechanism for how cognitive state is captured, modelled, and made available for further processing. And, like for my evolutionary narrative, this explanation is concrete enough that it can be easily simulated in computational models. Something I also hope to do.

Lastly, given the above, I think MMT is also more concrete in its explanation of the phenomenology of consciousness. Certainly, I provide a clearer explanation of why we only have conscious access to certain brain activity; and I'm able to make a clear prediction about the causal power of consciousness.

The one area that I'm not happy with yet is that I believe MMT is capable of significantly closing the explanatory gap, even if it can't close it entirely, but I haven't yet found the right way of expressing that.

Overall, science is a slow progression of small steps, most of which hopefully lead us in the right direction. I would suggest that MMT is a small step on from those other theories, and I believe it is in the right direction.

:100: :up:

A lot of areas of thinking are coming together, and I think you present a valuable sketch for considering the subject.

Quoting Malcolm Lett

I didn't at all think that you had ripped off Humphrey. I just thought you would appreciate the parallels in what he had to say there.

For context on my part, I've been thinking about the subject from a connectionist perspective, as an electrical engineer, for 37 years. It started with an epiphany I had after studying a bit about information processing in artificial neural networks. I recognized that a low level difference in neural interconnection within my brain might well explain various idiosncracies about me. I researched learning disabilities and researched the neuropsych available at the time, but it was in a bad state by comparions with today. It wasn't until about 12 years ago, that my wife presented a pretty reasonable case for me having, what at the time was called Asperger's syndrome. And it wasn't until about a year ago that I happened upon empirical evidence for the sort of low level variation in neural interconnection that I had expected to find explaining idiosyncracies I have, is associated with autism.

I was foreshadowing Kahneman's two systems view (discussed in Thinking, Fast and Slow) years before the book came out. I had come to a similar view to Kahneman's except I came at it from a much more neuropsychology based direction, compared to the more psychological direction Kahneman was coming from.

Anyway, I'm much more inclined to a connectionist view than a computationalist view. I was glad to see that you noted the blurriness involved in the issues you are trying to sketch out, but as I said, it seems like a good model for consideration.

Thanks. I really appreciate the kind words. The biggest problem I've had this whole time is getting anyone to bother to read my ideas enough to actually give any real feedback.

That's a cool story of your own too. It goes to show just how powerful introspective analysis can be, when augmented with the right caveats and some basic third-person knowledge of the architecture that you're working with.

Quoting RogueAI

Great question. MMT is effectively a functionalist theory (though some recent reading has taught me that "functionalism" can have some pretty nasty connotations depending on its definition, so let me be clear that I'm not defining what kind of functionalism I'm talking about). In that sense, if MMT is correct, then consciousness is multi-realizable. More specifically, MMT says that any system with the described structure (feedback loop, cognitive sense, modelling, etc) would create conscious contents and thus (hand-wavy step) would also experience phenomenal consciousness.

A structure that exactly mimicked a human brain (to some appropriate level) would have a consciousness exactly like humans, regardless of its substrate. So a biological brain, a silicon brain, or a computer simulation of a biological or silicon brain, would all experience consciousness.

Likewise, any earthling animal with the basic structure would experience consciousness. Not all animals will have that structure however. As a wild guess, insects probably don't. All mammals probably do. However, their degree of conscious experience and the characteristics of it would differ from our own - ie: not only will it "feel" different to be whatever animal, it will "feel" less strongly or with less clarity. The reason is that consciousness depends on the computational processes, and those processes vary from organism to organism. A quick google says that the human brain has 1000x more neurons than a mouse brain. So the human brain has way more capacity for modelling, representing, inferring, about anything. I've heard that the senses of newborn humans are quite underdeveloped, and that they don't sense things as clearly as we do. I imagine this is something like seeing everything blurry, but that all our senses are blurry, that one sense blurs into another, and that even our self awareness is equally blurry. I imagine that it's something like that for other animals' conscious experience.

I should also mention a rebuttal that the Integrated Information Theory offers to the suggestion that computers could be conscious. Now I suspect that many here strongly dislike IIT, but it still has an interesting counter-argument. IIT makes a distinction between "innate" state and state that can be manipulated by an external force. I'm not sure about the prior version but it's latest v4 makes this pretty clear. Unfortunately I'm not able to elaborate on the meaning of that statement, and I'm probably misrepresenting it too, because ...well... IIT's hard and I don't understand it any better than anyone else. In any case, IIT says that its phi measure of consciousness depends entirely on innate state, excluding any of the externally manipulatable state. In a virtual simulation of a brain, every aspect of brain state is manipulated by the simulation engine. Thus there is no innate state. And no consciousness.

Now, I don't understand their meaning of innate state very well, so I can't attack from there. But I take issue at the entire metaphor. A computer simulation of a thing is a complicated process that manipulates state held on various "state stores", shall we say. A brain is a complicated process involving atomic and sub-atomic electromagnetic interactions that work together to elicit more macro-level interactions and structures in the form of the structure of neurons and synapses, their bioelectrical signaling. Those neurons + synapses are also a form of "state store" in terms of learning through synaptic plasticity etc. Now, the neurotransmitters that can thrown across synaptic cleft are independent molecules. Those independent molecules play an external force against the "state store" of those synaptic strengths. In short, I think it can be argued (better than what I'm doing here) that atomic and subatomic electromagnetic interactions also just "simulate" the biochemical structures of neurons which also just "simulate" minds. Many IIT proponents are panpsychists -- the latest v4 version of IIT states that as one of its fundamental tenets (it just doesn't use that term) -- so their answer is something that depends on that tenet. But now we're on the grounds of belief, and I don't hold to that particular belief.

Thus, IITs distinction between innate and not-innate state, whatever it is, doesn't hold up, and it's perfectly valid to claim that a computer simulation of a brain would be conscious.

I recommend checking out @Pierre-Normand's thread on Claude 3 Opus. I haven't bit the bullet to pay for it to have access to advanced features that Pierre has demonstrated, but I've been impressed with the results of Pierre providing meta-management for Claude.

I have asked Claude 3 (Sonnet) for criticism of a half baked theory of mine and I thought the results were pretty good.

Anyway, I can empathize with the difficulty in finding people interested in thinking seriously about such things. I think AI is inevitably going to result in much wider consideration of these sorts of topics than has been the case. So you've got that going for you.

It seems like the entire "process" described, every level and aspect is the Organic functionings of the Organic brain? All, therefore, autonomously? Is there ever a point in the process--in deliberation, at the end, at decision, intention, or otherwise--where anything resembling a "being" other than the Organic, steps in?

Secondly, is the concept of self a mental model? You differentiate the self from the body, identify it as the Dominant whole of which the body is a part, was that just for the sake of the text, or how do you think of the self, if not just a mental model?

Quoting Malcolm Lett

I've read some of that discussion but not all of it. I haven't seen any examples of meta-management in there. Can you link to a specific entry where Pierre-Normand provides meta-management capabilities?

I assume that you are referring to the difference between the known physical laws vs something additional, like panpsychism or the cartesian dualist idea of a mind/soul existing metaphysically. My personal belief is that no such extra-physical being is required. In some respect, my approach for developing MMT has been an exercise in the "design stance" in order to prove that existing physical laws are sufficient to explain consciousness. Now I can't say that MMT achieves that aim, and the description in that blog post doesn't really talk about that much either. If you are interested, I made a first attempt to cover that in Part VI of my much longer writeup. I don't think it's complete, but it's a start.

Quoting ENOAH

Absolutely. I think that's a key component of how a mere feedback loop could result in anything more than just more computation. Starting from the mechanistic end of things, for the brain to do anything appropriate with the different sensory inputs that it it receives, it needs to identify where they come from. The predictive perception approach is to model the causal structure that creates those sensory inputs. For senses that inform us about the outside world, we thus model the outside world. For senses that inform us about ourselves, we thus model ourselves. The distinction between the two is once-again a causal one - whether individual discovers that they have a strong causal power to influence the state of the thing being modeled (here I use "causal" in the sense that the individual thinks they're doing the causing, not the ontological sense).

Alternatively, looking from the perspective of our experience, it's clear that we have a model of self and that we rely upon that. This is seen in the contrast between our normal state where all of our body movement "feels" like it's governed by us, versus that occasional weird state where suddenly we don't feel like one of our limbs is part of our body or that it moved without volition. It's even more pronounced in the phantom limb phenomenon. These are examples of where the body self models fail to correlate exactly with the actual physical body. There's a growing neuroscientific theory that predictive processes are key to this. In short, the brain uses the efference copy to predict the outcome of an action on the body. If the outcome is exactly as expected, then everything is fine. Otherwise it leads to a state of surprise - and sometimes panic. I'll link a couple of papers at the bottom.

Hallucination of voices in the head could be an example of a "mind-self model" distortion according to exactly the same process. We hear voices in our head all the time, as our inner monologue. We don't get disturbed by that because we think we produced that inner monologue - there's a close correlation between our intent (to generate inner monologue) and the effect (the perception of an inner monologue). If some computational or modelling distortion occurs that the two don't correlate anymore, then we think that we're hearing voices. So there's a clear "mind-model", and this model is related somehow to our "self model". I hold that this mind-model is what produces the "feels" of phenomenal consciousness.

I don't make an attempt to draw any detailed distinctions between the different models that the brain develops; only that it seems that it does and that those models are sufficient to explain our perception of ourselves. Out of interest, the article by Anil Seth that I mentioned earlier lists a few different kinds of "self" models: bodily self, perspectival self, volitional self, narrative self, social self.

Klaver M and Dijkerman HC (2016). Bodily Experience in Schizophrenia: Factors Underlying a Disturbed Sense of Body Ownership. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 10 (305). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00305

Synofzik, M., Thier, P., Leube, D. T., Schlotterbeck, P., & Lindner, A. (2010). Misattributions of agency in schizophrenia are based on imprecise predictions about the sensory consequences of one's actions. Brain : a journal of neurology, 133(1), 262271. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awp291

Understood. And FWIW, I currently

agree

Quoting Malcolm Lett

It's reasonable to me. My concerns about it are directed at myself, and whether I understand the details sufficiently. I read both your first post and the link, and should reread etc. But from my understanding it's persuasive. I believe there are reasonable, plus probably cultural, psychological, bases for "wanting" there to be more than physical, but still I find it strange that we [still?] do. Even how you intuitively knew you'd better clarify "in your opinion no need for extra physical."

Quoting Malcolm Lett

Very much with you

Quoting Malcolm Lett :up:

And so you didn't mean the "self" was

this severable thing, "part" of the Body, other than the model. No need to reply unless to clarify.

Thank you

Yes, I hope someone's done a thorough review of that from a psychological point of view, because it would be a very interesting read. Anyone has any good links?

Off the top of my head, I can think of a small selection of reasons why people might "want" there to be more:

* Fear of losing free-will. There's a belief that consciousness, free-will, and non-determinism are intertwined and that a mechanistic theory of consciousness makes conscious processing deterministic and thus that free-will is eliminated. This unsurprisingly makes people uncomfortable. I'm actually comfortable with the idea that free-will is limited to the extent of the more or less unpredictable complexity of brain processes. So that makes it easier for me.

* Meaning of existence. If everything in life, including our first-person subjective experience and the very essence of our "self", can be explained in terms of basic mechanistic processes - the same processes that also underly the existence of inanimate objects like rocks - then what's the point of it all? This is a deeply confronting thought. I'm sure there's loads of discussions on this forum on the topic. On this one I tend to take the ostrich position - head in sand; don't want to think about it too much.

As an aside, the question of why people might rationally conclude that consciousness depends on more than physical (beyond just "wanting" that outcome) is the topic of the so-called "Meta-problem of Consciousness". Sadly I've just discovered that I don't have any good links on the topic.

The "litmus test" that I refer to in the blog post is a reference to that. Assuming that consciousness could be explained computationally, what kind of structure would produce the outcome of that structure inferring what we do about the nature of consciousness? That has been my biggest driving force in deciding how to approach the problem.

It seems no more necessary than the "first level" I.e. the hard problem itself. It's a fundamental misunderstanding or misguided approach to Consciousness to begin with, viewing it as the primary of human existence. Probably rooted in those quasi psychological reasons you suggested. Even in broader philosophy the objects of the fears of loss are imagined 1) from a misunderstanding of the workings of the human mind, and 2) also, as "defense mechanisms" to shield us from the primary fear of loss, the loss of self.

But then that begs the meta meta question, why does consciousness cling to the self and all of those hypotheses which follows? Answering it might lead to another meta, and so on.

I think that strong identification with self, a mental model, is built (evolved) into the structure/function, because it promoted the efficient and prosperous system that said consciousness is today, and still evolving.

I might diverge from you (I cannot tell), in

"characterizing" or "imagining for the purpose of discussion" that evolution as taking place exclusively in/by the brain, notwithstanding our mutual rejection of dualism. But that's for another discussion.

https://naturalism.org/resources/book-reviews/consciousness-revolutions

Also, a short lecture by Metzinger summarizing the central idea of 'self-modeling' ...

Thoughts?

@bert1 @RogueAI @Jack Cummins @javi2541997 @Wayfarer

I only meant meta-management in a metaphorical sense, where Pierre is providing meta-management to Claude 3 in an external sense, via feedback of previous discussions.

I very much concur with Metzinger.

This thread doesn't seem to be going anywhere, so I'll post the usual stuff I post when someone claims this.

If a simulation is conscious, then that means a collection of electronic switches is conscious. That is to say that if you take enough switches, run an electric current through them, and turn them on and off in a certain way, the pain of stubbing a toe will emerge.

Isn't this already, prima facie, absurd?

Well yeah, because it's a straw man you have setup to knock down. It doesn't have anything to do with seriously thinking about the subject.

I'm not competent to critique your theory, much less to "roast" it. So, I'll just mention a few other attempts at computer analogies to human sentience.

The April issue of Scientific American magazine has an article by George Musser entitled A Truly Intelligent Machine. He notes that "researchers are modeling AI on human brains". And one of their tools is modularity : mimicking the brain's organization into "expert" modules, such as language and spatio-visual, which normally function independently, but sometimes merge their outputs into the general flow of cognition. He says, "one provocative hypothesis is that consciousness is the common ground". This is a reference to Global Workspace Theory (GWT) in which specialty modules, e.g. math & language, work together to produce the meta-effect that we experience as Consciousness. Although he doesn't use the fraught term, this sounds like Holism or Systems Theory.

Musser asks, in reference to GWT computers, "could they inadvertently create sentient beings with feelings and motivations?" Then, he quotes the GWT inventor, "conscious computing is a hypothesis without a shred of evidence". In GWT, the function of Meta-management might be to integrate various channels of information into a singular perspective. When those internal sub-streams of cognition are focused on solving an external problem, we call it "Intention". And when they motivate the body to act with purpose to make real-world changes, we may call it "Causality". Some robots, with command-line Intentions and grasping hands, seem to have the autonomous power to cause changes in the world. But the ultimate goal of their actions can be traced back to a human programmer.

In 1985, computer theorist Marvin Minsky wrote The Society of Mind, postulating a collection of "components that are themselves mindless" that might work together to produce a Meta-manager (my term) that would function like human Consciousness. In his theory, their modular inputs & outputs would merge into a Stream of Consciousness (my term). Yet one book review noted that : "You have to understand that, for Minsky, explaining intelligence is meaningless if you cannot show a line of cookie crumbs leading from the 'intelligent' behavior to a set of un-intelligent processes that created it. Clearly, if you cannot do that, you have made a circular argument." {my italics}

In computer engineer/philosopher Bernardo Kastrup's 2020 book, Science Ideated, he distinguishes between "consciousness and meta-consciousness". Presumably, basic sentience is what we typically label as "sub-consciousness". He then notes that meta-C is a re-representation of subconscious elements that are directed by Awareness toward a particular question or problem. He also discusses the counterintuitive phenomenon of "blindsight", in which patients behave as-if they see something, but report that they were not consciously aware of the object. This "limited access" may indicate that a> subconscious Cognition and b> conscious Awareness are instances of a> isolated functions of particular neural modules, and b> integrated functions of the Mind/Brain system as a whole. :nerd:

:up: :up:

Quoting Gnomon

Maybe you missed the link posted by @ "wonderer1" ...

https://aeon.co/essays/how-blindsight-answers-the-hard-problem-of-consciousness

If someone believes a simulation of a working brain is conscious, would this be a fairly accurate description of what the person believes: "to say that a simulation of a working brain is conscious is to say a collection of electronic switches is conscious. That if you take enough switches, run an electric current through them, and turn them on and off in a certain way, the pain of stubbing a toe will emerge."

ChatGPT

Yes, that description captures the essence of the belief that a simulation of a working brain could be conscious. It implies that consciousness arises from the complex interactions of physical components, such as electronic switches in the case of a simulation, rather than from some non-physical or supernatural source. This perspective aligns with the idea that consciousness is an emergent phenomenon resulting from the arrangement and activity of the underlying components, similar to how the experience of pain emerges from the activity of neurons in a biological brain.

Thanks for the link. https://aeon.co/essays/how-blindsight-answers-the-hard-problem-of-consciousness

The article is interesting, and it may offer some insight as to why the Consciousness problem is "hard". The notes below are for my personal record, and may interpret the article's implications differently from yours.

The article refers to Blindsight as a "dissociation" (disconnection) between physical Perception (biological processing of energetic inputs) and metaphysical Sensation*1 (conception ; awareness) {my italics added}. And that seems to be where easy physics (empirical evidence) hands-off the baton of significance (semiotics) to hard meta-physics (non-physical ; mental ; rational ; ideal). Apparently the neural sensory networks are still working, but the transition from physical Properties to metaphysical Qualia doesn't happen*2.

Of course, my interpretation, in terms of metaphysics, may not agree with your understanding of the "phenomenon" which lacks the noumenon (perceived, but not conceived). The author suddenly realized that "Perhaps the real puzzle is not so much the absence of sensation in blindsight as its presence in normal sight?" That's the "Hard Problem" of Consciousness.

The article describes a primitive visual system that evolved prior to warm-blooded mammals, in which the cortex may represent a social context for the incoming sensations. Presumably, social animals --- perhaps including some warm-blooded dinosaurs, and their feathered descendants)*4 --- are self-conscious in addition to basic sub-conscious. The author says "I call these expressive responses that evaluate the input sentition."*5 The evaluation must be in terms of Personal Relevance. Non-social animals may not need to view themselves as "persons" to discriminate between Self and Society.

The author refers to Integrated Information Theory (IIT), which seems to assume that some high-level functions of brain processing supervene --- as a holistic synergy --- on the chemical & electrical activities of the neural net*6. As I interpret that insight, Perception is physical*7, but Conception is metaphysical*8. i.e. Holistic. System functions are different from Component functions. Some Bits of Neural data are useless & valueless (irrelevant) until organized into a holistic system of Self + Other. It puts the data into a comprehensive, more inclusive, context.

Like a cell-phone Selfie, the broad-scope perspective puts Me into the picture. Neuron sensations (data) are impersonal ; Mind feelings (qualia) are personal. Evolutionary survival is enhanced by the ability to see the Self in a broader milieu, as a member of a social group : a community*9. Feeling is a personally relevant evaluation of incoming sensations. This ability to re-present physical as personal is the root of consciousness. :smile:

Excerpts from An evolutionary approach to consciousness can resolve the hard problem with radical implications for animal sentience, by Nicholas Humphrey

*1. "[i]Sensation, lets be clear, has a different function from perception. Both are forms of mental representation : ideas generated by the brain. But they represent they are about

very different kinds of things. . . . Its as if, in having sensations, were both registering the objective fact of stimulation and expressing our personal bodily opinion about it.[/i]"

Note --- In blindsight, the objective data is being processed, but the subjective meaning is missing. Terrence Deacon defines "aboutness" as a reference to something missing, "incompleteness", a lack that needs to be filled.

*2. "The answer is for the responses to become internalised or privatised. . . . . In this way, sentition evolves to be a virtual form of bodily expression yet still an activity that can be read to provide a mental representation of the stimulation that elicits it."

Note --- Virtual = not real ; ideal. Representation = copy, not original

*3. "In attempting to answer these questions, were up against the so-called hard problem of consciousness: how a physical brain could underwrite the extra-physical properties of phenomenal experience."

Note --- What he calls "extra physical" I'm calling Meta-physical, in the sense that Ideas are not Real.

*4. My daddy used to say that "chickens wake-up in a new world every day". Maybe their primitive neural systems don't register meaning in the same way as hound dogs.

*5. "To discover whats happening to me, the animal has only to monitor what Im doing about it. And it can do this by the simple trick of creating a copy of the command signals for the responses an efference copy that can be read in reverse to recreate the meaning of the stimulation."

Note --- Efference copy is a feedback loop, that adds Me to data : supervenience.

*6. "it {consciousness) involves the brain generating something like an internal text, that it interprets as being about phenomenal properties."

Note --- Terrence Deacon " . . . variously defines Reference as "aboutness" or "re-presentation," the semiotic or semantic relation between a sign-vehicle and its object." https://www.informationphilosopher.com/solutions/scientists/deacon/

*7. "Sensation, lets be clear, has a different function from perception. Both are forms of mental representation : ideas generated by the brain. But they represent they are about very different kinds of things. Perception which is still partly intact in blindsight is about whats happening out there in the external world: the apple is red; the rock is hard; the bird is singing. By contrast, sensation is more personal, its about whats happening to me and how I as a subject evaluate it

Note --- In this case, "sensation" is the visceral Feeling of What Happens to yours truly.

*8. "ask yourself: what would be missing from your life if you lacked phenomenal consciousness?"

Note --- You would lack a sense of Self and self-control and ownership, which is essential for humans in complex societies.

*9. "What about man-made machines?"

Note --- Sentient machines could possibly emerge as they become dependent on social groups to outsource the satisfaction of some of their personal needs.

And yet ideas obviously exist. If they're not physical, what are they? Are you a substance dualist?

Yes*1. Physical substances are made of Matter, but what is matter made of?*2 Einstein postulated that mathematical Mass (the essence of matter) is a form of Energy. And modern physicists --- going beyond Shannon's engineering definition --- have begun to equate Energy with Information. In that case, Causal Information is equivalent to Energy as the power to transform : some forms are Physical (matter + energy) and other forms are Meta-Physical (mental-ideal).

Philosophical "substance" is made of something immaterial. Plato called that something "Form", but I call it "EnFormAction" (the power to transform). Which you can think of as "Energy", if it suits you. Aristotle concluded that material objects consist of a combination of Hyle (stuff) and Morph (form)*3*4. What kind of "stuff" do you think conceptual Ideas consist of? Is it the same substance that elementary particles, like Electrons & Quarks, are made of?

Ideas do "exist" but in a different sense from physical Matter. They are intangible & invisible & unreal (ideal) --- so we know them only by reasoning or by communication of information --- not by putting them under a microscope or dissecting with a scalpel.

I can also answer "no" to your question, because essential Energy is more fundamental than substantial Matter. From that perspective, I'm an Essence Monist. :smile:

*1. Substance Dualism :

Substance dualists typically argue that the mind and the body are composed of different substances and that the mind is a thinking thing that lacks the usual attributes of physical objects : size, shape, location, solidity, motion, adherence to the laws of physics, and so on.

https://iep.utm.edu/dualism-and-mind/

*2. Substance :

To account for the fundamental whatness of a thing, Plato posited an unchanging form or idea as the underlying and unchanging substance. As all things within a person's reality are subject to change, Plato reasoned that the forms or unchanging basic realities concerning all things must not be located within this world.

https://openstax.org/books/introduction-philosophy/pages/6-1-substance

*3. Hyle + Morph ; Substance + Essence :

Matter is not substance, nor is any universal, nor is any combination of some form and some particular matter. Identifying a substance with its essence helps Aristotle to solve a difficulty about the unity of the individual sub-stance: over a period of time an ordinary substance is likely to change in some ways.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2184278

Note --- Modern dictionary "substance" refers to the Hyle, and omits the Form.

*4. Hylomorphism : (from Greek hyl?, matter; morph?, form), in philosophy, metaphysical view according to which every natural body consists of two intrinsic principles, one potential, namely, primary matter, and one actual, namely, substantial form.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/hylomorphism

Note --- In our modern context, it might make more sense to characterize Matter as Actual and Form as Potential. For Ari, "Actual" meant eternal & unchanging.

As I said before, I'm not qualified to comment on your theory in a technical sense. So, I'll just mention some possible parallels with an article in the current Scientific American magazine (04/24) entitled : A Truly Intelligent Machine. George Musser, the author, doesn't use the term "meta-management", but the discussion seems to be saying that Intelligence is more than (meta-) information processing. For example, "to do simple or rehearsed tasks, the brain can run on autopilot, but novel or complicated ones --- those beyond the scope of a single module --- require us to be aware of what we are doing". In a large complex organization, such supervision --- etymology, to see from above (meta-) --- is the role of upper management. And the ultimate decision-maker, the big-boss, is a Meta-Manager : a manager of managers.

Musser notes that, "consciousness is a scarce resource", as is the supervising time of the big boss, who can't be bothered with low-level details. Later, he says, "intelligence is, if anything, the selective neglect of detail" Which may be related to your item (3) Limited Access. So, researchers are advised to "go back to the unfashionable technology of 'discriminative' neural networks". Which may get back to your item (1) Intentionality. Intentional behavior requires discrimination between inputs & outputs : incoming low-level data and executive actions. After "all those irrelevant details are eliminated", the manager can focus on what's most important.

The article refers to a "key feature" of GWT (Global Workspace Theory) as a "configurator to coordinate the modules and determine the workflow". Again, the "Configurator" or optimizer or designer seems to be a high-level management position. That role also seems to require "self-monitoring". The GWT expert speculates that "consciousness is the working of the configurator". Musser notes that, "those capacities . . . aren't relevant to the kinds of problems that AI is typically applied to". So, the GWT guy adds, "you have to have an autonomous agent with a real mind and a control structure for it" Such executive agency also requires the power to command, which your item (2) calls "causality", the influence determining subsequent effects.

Neuroscientist Anil Seth makes an important philosophical observation : "Consciousness is not a matter of being smart, it's equally a matter of being alive". And that makes the "hard problem" of creating consciousness even harder. Perhaps requiring divine powers. Or a bolt of lightning : "it's alive!!!" :joke:

Quoting bert1

I think that just getting some clarity about the functional aspects of consciousness would be a huge leap forwards, regardless of whether they explain the phenomenal aspects. I'm regularly frustrated at various discussions that necessarily go off into hypotheticals because they have nothing agreed upon to ground the discussion. For example, if you're trying to understand the phenomenality of consciousness, but you don't have an agreed reason for why the functional aspects of it exist, or what they do, then you are at a loss to where to define the scope of what is and isn't consciousness -- a classic case is Block's seminal paper that tries to distinguish between access and phenomenal consciousness. His arguments about P-Cs existing without A-Cs, or vice versa, can only be made because we don't have clear boundaries of what consciousness is.

My point is that the work of the sort of Metzinger's or my own, if we could find some way to test the theories and pin down the details, would help a lot to define those boundaries at the physical and functional level. Then we'd be in a better position to figure out what P-Cs is.

Quoting 180 Proof

I'm not familiar with his theory. I've just watched the TED talk video so far. The basic idea of us developing a self-model, developing models of the world, and seeing the world through those models is precisely what I'm basing my theory on. It's also the same idea put forward by Donald Hoffman's User Interface Theory of Perception. I'll read for fully his theory though - the "tunnel" analogy is interesting. Also interesting is his suggestion that the processes that take our raw perceptions and turn them into our modelled interpretation of the world is "too fast" for us to analyse (introspectively).

Yes I think that's right, the two seems very similar in terms of the functional story. But their claims about consciousness seem very different (but I haven't studied either properly - these are just first impression). Contrasting panpsychism with conscious realism is interesting, and something I haven't thought about enough.

Just out of interest, I'll have a go.

So, let's say that this kidney simulation is 100% accurate of a real kidney, to the level of, say, molecules. And that this kidney simulation has a rudimentary simulation of its context operating in a body, so that if a simulated kidney were to pee, then it could. In this example, the kidney would indeed pee, not on his desk, but inside the simulation.

If we take as an assumption (for the sake of this thought experiment) that consciousness is entirely physical, then we can do the same thing with a conscious brain. This time simulate the brain to the molecular level, and again provide it some rudimentary body context so that the simulated brain thinks it's operated inside a body with eyes, ears, hands, etc. Logically, this simulation thus simulates consciousness in the brain. That's not to say that the simulated brain is conscious in a real world sense, but that it is genuinely conscious in its simulated world.

The question is what that means.

Perhaps a simulation is nothing but a data structure in the computer's memory. So there is nothing that it "feels like" to be this simulated brain -- even though there is a simulation of the "feels like" nature.

Alternatively. David Chalmer's has a whole book arguing that simulations of reality are themselves reality. On that basis, the simulation of the brain and its "feels like" nature are indeed reality -- and the simulated brain is indeed conscious.

A third argument appeals to a different analysis. Neurons can be said to simulate mind states, in something similar to the same way that a computer simulation of a brain would. I'm appealing to the layered nature of reality. No single neuron is a mind, and yet the collection of billions of neurons somehow creates a mind (again, I'm assuming physicalism here). Likewise, neurons are not single discrete things, but collections of molecules held together by various electromagnetic forces. Trillions of molecules are floating through space in the brain, with arbitrary interaction-based grouping creating what we think of as object boundaries - constructing what we call neurons, glial cells, microtubules, etc. These molecules "simulate" neurons etc. In all of that, there is no such thing as a "mind" or "consciousness" as any kind of object in the "real world". Those things exist as simulations generated by all these free-floating molecule-based simulations of neural-networks. Thus, the computer simulation of a conscious mind is no more or less real than a molecular simulation of a mind.

At the level of the review summary of Metzinger's work, there's not a lot that's unique compared to what various others have written about. It's becoming a well narration of our current neuroscientific understanding. That's not too say that his particular telling of the story isn't valuable, but I do feel a sense of frustration when I read something suggesting that it's one particular person's ideas when actually these are already ideas in the common domain.

This is more of a reflection for myself. I chose at an early stage that it was going to be very convoluted to tell my particular narrative based on other's works because they all had extra connotations I wanted to avoid. I would have to spend just as much time talking about which parts of those other theories should be ignored in terms of my story. But I can see the frustration that that can create. I shall need to do better to be clear which parts are novel.

A second thought is about his description of the key evolutionary function of the phenomenal experience that he attributes to the self model. I suspect his books make a better case, but the review suggests he may have fallen into a common trap. The phenomenal and subjective natures of our experience are so pervasive that it can be hard to conceptually separate them from the functions that we're trying to talk about. He says that we need the experience of self to be attached to our perceptions in order to function. But does he lay out clearly why that is the case? It's not a given. A simple robot could be granted access to information that delineates it's physical form from that of the environment without any of the self modelling. Even if it models the "self", it doesn't follow that it then "experiences" the self in any way like we do. I'm all for suggesting that there is a computational basis to that experience, but a) the mechanisms need to be explained, and b) the functional/evolutionary benefit for that extra step needs to be explained.

That's what I've tried to do with the more low-level handling of the problem in MMT. Though even then there are some hand-wavy steps I'm not happy with.

Metzinger's books look like an excellent read. Thankyou for sharing the links.

The problem here is that simulated urination/urine is not urine (Kastrup's point that the simulated kidney will never pee on his desk), so if simulated urine is not actual urine, simulated consciousness would not be actual consciousness.

Also, you speak of "inside the simulation". Imagine you're running a simulation of a tornado. Then all the minds in the universe disappear, but the computer the simulation is running on is still active. With all the minds gone, is there still a simulation of a tornado going on? Or is it just a bunch of noise and pixels turning off and on? I think the latter, and this goes back to my point that any simulation is ultimately just a bunch of electric switches turning off and on in a certain way. It takes a mind to attach meaning to the output of those switching actions.

:up:

I appreciate your frustration. Still, I appreciate that Metzinger is able to communicate this way of looking at things effectively.

That's a matter of opinion. Your statement depends on the idea that consciousness is special in some way - beyond normal physics - and that it's our consciousness that creates meaning in the universe.

An alternative view is that physicalism fully explains everything in the universe, including consciousness (even if we don't know how), and under that view the simulation of the tornado is no different with/without human consciousness. Semiotics explains that data representations have no meaning without something to interpret them. So a computer simulation of a tornado without something to interpret the result certainly would be lacking something - it would just be data noise without meaning. But the thing doing the meaning interpretation doesn't have to be a human consciousness. It could just as easily be another computer, or the same computer, that is smart enough to understand the need to do tornado simulations and to examine the results.

The urination example is a nice "intuition pump" (as Dennet calls them), but like many intuition pumps it doesn't hold up against closer scrutiny. The point I was trying to make about conscious simulations is that it's not a given that there's a substantial difference between the simulation in a silicon computer versus a simulation in a molecular computer (aka biology). If you hold to the idea that consciousness is purely physical, then this argument doesn't seem so strange.

I might be wrong, but I think most of us are intuitively looking at the "simulation of urination" example in a particular way: that the computer is running in our world -- let's call it the "primary world" -- and that the simulated world that contains either the simulated urination or the simulated consciousness is a world nested within our own -- so let's call it the "nested world". On first glance that seems quite reasonable. Certainly for urination. But on closer inspection, there's a flaw. While the simulated world itself is indeed nested within the primary world, the simulated urine is not nested within primary world urine. Likewise, the simulated consciousness is not nested within the primary world consciousness. Now, if you take my argument about molecules acting as a mind simulator, then the primary world consciousness in my brain is a sibling to the nested world consciousness.

There's a tree of reality:

https://xkcd.com/505/

Is it possible to simulate consciousness by moving rocks around (or, as one of the members here claims, knocking over dominoes)?

Ciitation needed. Where has someone here claimed that consciousness can be simulated by knocking over dominoes?

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/893885

"Does anyone think a system of dominoes could be conscious? What I meant by a system of dominoes includes a machine that continually sets them up after they fall according to some program."

Quoting flannel jesus

What do you think, Wonderer? Could consciousness emerge from falling dominoes?

Incredible op!!! :sparkle: You have clearly poured a lot of thought into the matter, to great effect. I will read your blog post next, and your paper is on my list. I've had similar ideas, though not nearly at your level of depth and detail.

I think where we most sharply differ is in the nature of deliberation.

In your account, deliberation is something that chugs along on its own, without awareness. It is only via a meta management process that a predictive summation enters awareness.

But this is at odds with my introspective account of deliberation. Deliberation itself seems to be explicitly phenomenal: I speak to my self (auditory), and this self talk is often accompanied by imagery (visual). The conscious brain seems to speak to itself in the same "language" that the unconscious brain speaks to it: the language of sensation.

Is your idea that phenomena such as self talk is a model of the unconscious deliberation that is actually taking place? This does not seem to do justice to the power that words and images have as tools for enabling thought, not just in providing some sort of executive summary. Think of the theory that language evolved primarily not for communication but as a means of enabling thought as we know it. Can meta management explain the gargantuan cognitive leap we enjoy over our nearest animal neighbors?

If deliberation is phenomenal, then there is no need for this meta management process. Deliberation enters awareness in a manner that is co-equal with the phenomenal models of the external world. If deliberation goes off the rails, then the executive brain can regulate it, since deliberation is at least partially voluntary.

The evolutionary novelty enabling deliberation would be the ability of the executive brain to insert phenomenal models into it's own inputs. This explains the relative feebleness of especially visual imagery: the same predictive modeling systems used by sensation are *not* reused by the executive brain. Rather, it (sometimes quite crudely) mimics them. Audio, being less information dense, is more amenable to this mimicry.

Since the cost/benefit ratio of this change seems very favorable, we should expect at least crude deliberation to be widespread in nature. Adding language as a deliberative tool is where the real cognitive explosion happened.

Here is a rough sketch of my alternative take. (I see I used "rumination" for "deliberation". )

remove duplicates online

Quoting hypericin

Sure. That is indeed a different take. I'm taking what I like to think of as a traditional scientific approach, otherwise known as a reductionist materialist approach. Like anyone in this field, I'm driven by a particular set of beliefs that is driven by little more than intuition - my intuition is that reductive scientific methods can explain consciousness - and so a big motivation -- in fact one of the key drivers for me - is that I want to attempt to push the boundaries of what can be explained through that medium. So I explicitly avoid trying to explain phenomenology based on phenomenology.

Quoting hypericin

Meta-management is just the start - or more accurately an intermediary step somewhere along the way. The multi-model internal representations that we use for thought - for deliberation - are an equally important part of intelligence and of the contents and depth of our conscious experience. Likewise are the mechanisms for attentional control, memory, and sorts of other key features of intelligence. As we know from evolution, these things tend to evolve together in a positive feedback loop. So I wouldn't say that my theory diminishes any of that, rather that it offers a theory of just one part.

There's also the possibility that there are multiple feedback loops involved that operate under different regimes. For example, there's an interesting dichotomy in discussions related to various higher-order theories and other meta-cognitive ideas between first-order and second-order processes and representations. HOT for example proposes that consciousness is a second-order representation that is presumably additionally second-order processed. But then there's rebuttals by others suggesting that the effects of HOTs could be achieved through first-order mechanisms. MMT is perhaps a little peculiar in that it constructs a second-order representation (the summary step in the feedback loop), but then feeds it into first-order processing.

In contrast, attention is a mechanism that also needs to monitor and manipulate cognitive processing. The neuroscientific literature at the moment I believe favours a first-order representation, but arguably attention is a second-order process.

Well, I'm being a bit waffly, but the point I'm trying to make is that there's good reason to suspect that the brain includes multiple different kinds of macro-scale feedback loops that operate in different ways. I suspect a more complete theory would acknowledge that all of those different ways contribute to the final result.Quoting hypericin

There's a great 2023 book by Max Bennet, A Brief History of Intelligence. It lays out a very approachable story of how various aspects of human intelligence involved, going all the way back to the first worms. They also mention a number of theories of how language evolved and how it might be involved with thought.

I absolutely agree with your intuition.

Of course, there is a difference between explaining self-awareness and explaining phenomenology. I am trying to explain self-awareness, not phenomenology, with phenomenology. Your theory is clearly an explanation of self-awareness, much less clearly an explanation of phenomenology. As you say, you have an intuition of how it might partly explain it, but struggle to articulate it.

Quoting Malcolm Lett

My concern was that you were treating what we in the everyday sense term "deliberation", such as self talk, as epiphenomenal, as the "cognitive sense" corresponding to the real work happening behind the scenes. Was that a misunderstanding? Is self talk not the sort of deliberation you had in mind?

Consider the fact that traditional science doesn't permit scientific explanations to be represented or communicated in terms of indexicals, because indexicals do not convey public semantic content.

Wittgenstein made the following remark in the Philosophical Investigations

410. "I" is not the name of a person, nor "here" of a place, and

"this" is not a name. But they are connected with names. Names are

explained by means of them. It is also true that it is characteristic of

physics not to use these words.

So if we forbid ourselves from reducing the meaning of a scientific explanation to our private use of indexicals that have no publically shareable semantic content , and if it is also assumed that phenomenological explanations must essentially rely upon the use of indexicals, then there is no logical possibility for a scientific explanation to make contact with phenomenology.

The interesting thing about science education, is that as students we are initially introduced to the meaning of scientific concepts via ostensive demonstrations, e.g when the chemistry teacher teaches oxidation by means of heating a testtube with a Bunsen Burner, saying "this here is oxidation". And yet a public interpretation of theoretical chemistry cannot employ indexicals for the sake of the theory being objective, with the paradoxical consequence that the ostensive demonstrations by which each of us were taught the subject, cannot be part of the public meaning of theoretical chemistry.

So if scientific explanations are to make contact with phenomenology, it would seem that one must interpret the entire enterprise of science in a solipsistic fashion as being semantically reducible to one's personal experiences... In which case, what is the point of a scientific explanation of consciousness in the first place?

I'm not sure if you mean "epiphenomenal" in the same way that I understand it. The Cambridge dictionary defines epiphenomenal as "something that exists and can be seen, felt, etc. at the same time as another thing but is not related to it". More colloquially, I understand epiphenomenal to mean something that seems to exist and has a phenomenal nature, but has no causal power over the process that it is attached to. For either definition, is deliberation epiphenomenal? Absolutely not. I would place deliberation as the primary first-order functioning of the brain at the time that it is operating for rational thought. Meta-management is the secondary process, that it performs in addition to its deliberation. Neither are epiphenomenal - as they both perform very important functions.

Perhaps you are meaning to make the distinction between so-called "conscious and unconscious processing" in the form that is sometimes used in these discussions - being that the colloquial sense of deliberation you refer to is somehow phenomenally conscious in addition to the supposedly "unconscious" mechanical processes that either underly that deliberation or are somehow associated. If that is the intention of your question, then I would have to start by saying that I find distinction arbitrary and unhelpful.

MMT claims that when first-order cognitive processes are attended to through the meta-management feedback loop + cognitive sense, then that first-order cognitive process becomes aware of its own processing. At any given instant in time, deliberative processes may occur with or without immediately subsequent self-focused attention co-occurring. Regardless, due to the complex and chaotic* nature of deliberation, moments of self-focused attention will occur regularly in order to guide the deliberative process. Thus, over time the cognitive system maintains awareness over its overall trajectory. The granularity of that awareness differs by the degree of familiarity and difficulty of the problem being undertaken.

I claim that the self-focused attention and subsequent processing of its own cognitive state is what correlates with the phenomenal subjective experience. So all of those processes are conscious, to the degree of granularity of self-focused attention.

* - by "chaotic" I mean that without some sort of controlling feedback process it would become dissociated from the needs of the organism; that the state trajectory would begin to float unconstrained through cognitive state space, and ultimately lead to poor outcomes.

Does that answer your question?

https://xkcd.com/505/

I've been thinking about this over the last couple of days. On first glance I found that it inspired an intuition that no computer simulation could possibly be anything more than just data in a data structure. But it goes further and inspires the intuition that a reductive physicalist reality would never be anything more either. I'm not sure if that's the point you were trying to make, but I wanted to delve deeper because I found it interesting.

In the comic, Randal Munroe finds himself mysteriously ageless and immortal on a vast infinite expanse of sand and loose rocks. He decides to simulate the entire physical universe, down to sub-atomic particles. The implication is that this rock based universe simulation includes simulation of an earth-like planet with human-like beings. Importantly, the rocks are inert. Randal must move them, according to the sub-atomic laws of physics that he has deduced during his endless time to ponder.

So, importantly, the rocks are still just rocks. They have no innate meaning. It's only through Randal's mentality that the particular arrangement of rocks means anything.

In our physical reality, we believe that the sub-atomic particles interact according to their own energetic forces - there is no "hand of god" that does all the moving around. But they operate exactly according to laws of physics. In the thought experiment, Randal plays the personification of those laws. So it makes no material difference whether the subatomic particles move according to their energies in exact accordance with the laws of physics, or whether the "hand of god"/Randal does the exact same moving.

The rock-based simulation of reality operates according laws of physics that may be more complete than what we currently know but which we assume are entirely compatible with the dogma of reductive physicalism. According to that dogma, we believe that our real reality operates according to the same laws. Thus, the rock-based simulation and our reality are effectively the same thing. This leaves us with a conundrum - our intuition is that the rock simulation is just a bunch of inert objects placed in arbitrary and meaningless ways, it means nothing and carries no existence for any of the earths or humans that it supposedly simulates - at least not without some observer to interpret it. This means that the same applies to our reality. We're just a bunch of (effectively inert) subatomic particles arranged in arbitrary ways. It means nothing, unless something interprets it.

This kind of reasoning is often used as the basis for various non-physicalist or non-reductive claims. For example, because consciousness is fundamental and universal, and it is this universal consciousness that does the observing. Or perhaps the true laws of physics contain something that is not compatible with reductive physicalism.

These are both possibilities, and others alike.